No one could accuse Anselm Kiefer of being a miniaturist. The White Cube in Bermondsey is a large space and it’s packed full with the huge displays of his new exhibition, a response to his long-time admiration for James Joyce’s unreadable masterwork, Finnegans wake.

The Cube isn’t a cube at all, but an oblong. When you enter, you find yourself wandering, in sparse electric light, down a lengthy corridor. To each side there are metal cases, displays and vitrines filled with all kinds of detritus: ancient machinery, rusty plants and flowers, lumps of concrete, old bicycles. Most are ‘labelled’, in Kiefer’s own sometimes unreadable handwriting, with short quotations from the Wake. You peer at all these through the gloom and try, with limited success, to make some coherent connection between label and object. Visually this part of the show amounts to a retrospective encyclopedia of Kiefer’s work across the years, many themes being repeated from earlier exhibitions. The experience reminds you of walking through the store of a major archaeological museum, lined with shelves of artefacts excavated centuries ago, forgotten and obscure.

The procession of objects is broken at points to allow you access to large rooms on either side. One of them continues the museum store format, this time with displays piled much higher. The other rooms contain gigantic displays, in Kiefer’s ‘monumental’ mode. One is a scene of total destruction: giant beams and floors white concrete, smashed and contorted, and decorated with barbed wire and giant fossilised sunflowers. Ruin is a Kiefer staple, and people often connect it to the state of German cities at the time he was born, in 1945. Here the Joyce quotes are written on the walls. One of them reads ‘With earnestly conceived hopes’.

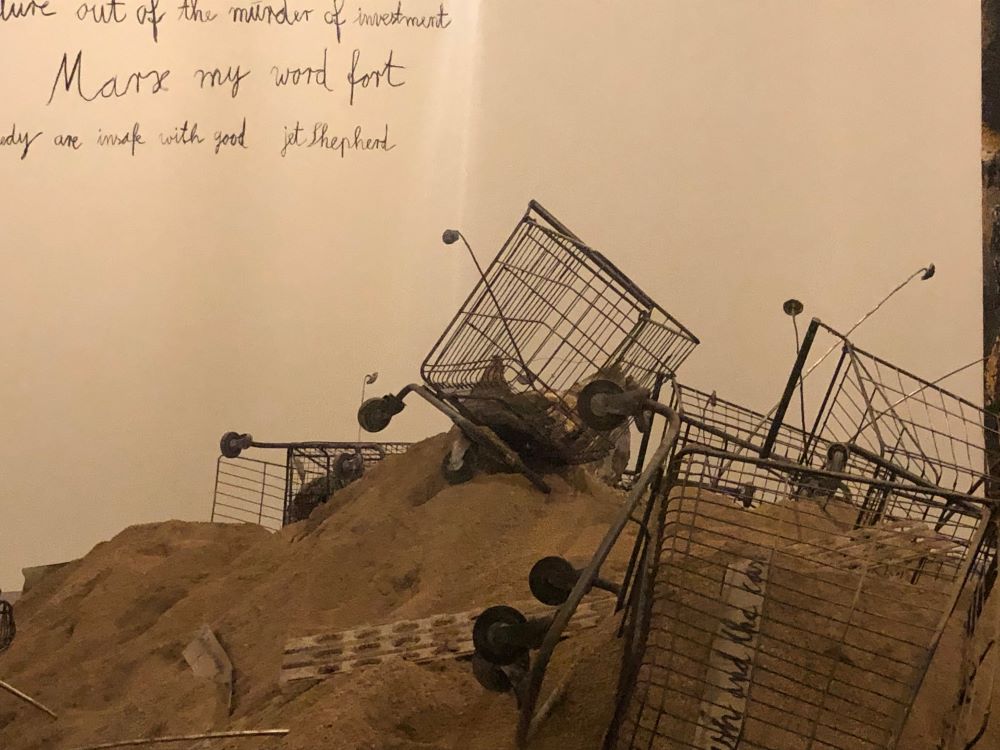

In another room, abandoned shopping trollies and a wheelchair project at odd angles from an immense pile of sand (this reminded me of Samuel Beckett rather than Joyce.) Part of one of the Finnegans wake quotations reads, ‘Marx my word fort’. A gigantic impasto’d painting faces the sand. It features a great crowd of people (refugees?) huddled below a great flash of light in the sky above. Abandoned shoes are fastened to the surface and hang in the space between flash and people.

The final room is different and features a long series of large ‘landscape’ paintings of tree-lined waterways, either rivers (one is labelled ‘Liffey’) or lakes. These carry a heavy and powerful presence, with their mix of gold and copper verdigris colouring. Are they views of Eden, immediately before the Fall (Kiefer picks out the Joyce quotes, ‘Phall if you but will, rise you must’ and ‘When Adam was delvin and his madameen spinning watersilts’)? Probably, because snakes, another Kiefer motif, slither across the metal ‘books’ that litter the centre of the room.

I found this a powerful and intriguing exhibition, but a puzzling one – for two reasons. Kiefer’s vision, on the surface at least, is a grim one. It speaks of destruction, death and dereliction. There are a few jokes, and no obvious ‘hopes’ on view. Finnegans wake is also about extinction (the clue is in the title), but Joyce’s novel is about so much more. For one thing, it’s also about rebirth, celebration and circularity (the clue is in the title), and there are always grounds for hope. The novel is famously itself circular, as the final words loop back into the first ones. But Kiefer doesn’t appear to offer us much to affirm renaissance and continuation of life, with the possible exception of the watery scenes, if you want to read them as a sign towards a better future.

The second puzzle is about style. Finnegans wake is also about play – most obviously the play of words. No other book in the world contains so many puns, and none can match the multilingual wordplay Joyce invented, based on the astonishing range of languages he was master of. The effect of this unending display of linguistic fireworks is overwhelming – it slows your reading pace down to a crawl, so that a single page is quite enough for one evening’s reading – but it’s also joyful, a celebration of the endless variety of language and its alter ego, life. Kiefer seems to have no visual answer to this multiplicity and enchantment. He’s too monolingual in his artistic expression to burst into jubilation.

It could be, though, that I’m not thinking hard enough. Kiefer insists that his smashed concrete ruins are ‘the beginning of something, not the end. It’s the beginning.’ As a small child he saw the rubble he lived in as a playground, the start of a new world. Similarly, his sunflowers, scattered all over this show, point, he says, to hope and light, even if at first sight they seem symbols of death. But it takes almost as much patience to divine this optimism in Kiefer’s work as it does to get to grips with Finnegans wake.

Leave a Reply