I’m not sure what other people think, but on the whole I’d say I was a person of fairly equable temper. But recently I’ve begun to realise that I’ve started having angry conversations about contemporary politics, especially politics as practised in Britain. This goes beyond just venting exasperation, like growling at the television when BBC News seems to take its line direct from Conservative Central Office or the Daily Mail. No, I mean raising my voice when having talking politics with friends – yes, at home with friends, not responding to rabid reactionaries in the street – and having to be restrained from shouting the same opinions at ever higher volumes.

What’s happening here, I ask myself. There seem to be two possibilities. You could argue that there’s now so much to be furious about in our current politics that it’s almost impossible to keep control of your temper, no matter how hard you try. Or maybe the fault lies with me. The politics is no worse than it’s ever been, but some change has happened in my own psychology or neurology. What I would have dismissed with a wave of the hand now gets under my skin and causes irritation or bursts out in a red rash.

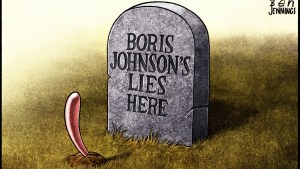

The first theory looks a strong one. After thirteen years of cruel, corrupt and incompetent Tory rule Britain looks like an ugly place, with little hope of becoming more beautiful. The word ‘rule’ isn’t right, of course. The government lost interest in governing some years ago, when Boris Johnson came to power. All that mattered to him, other than himself, was posturing, grand projets and electioneering. He was too lazy and mendacious to be interested in policy or the public good. Though, actually, the rot set in much earlier, when Brexitmania ruined the Tories’ gums and blackened their teeth. The extremists had taken over and any remaining moderates were driven away. By now Parliament has ceased to function, more or less, in part because there’s no legislation to discuss, and Rishi Sunak looks as if he can’t wait to get back to Goldman Sachs.

The man who started the rot, of course, was David Cameron, who thought the extremists could be silenced with a referendum. Cameron, too, was a lazybones, and the real damage in his time was done by the worst villain of the lot, George Osborne. Without Osborne’s duplicitous ‘austerity’ programme – there was plenty of welfare for bankers, but no money left for anyone less fortunate – we wouldn’t have had Brexit, food banks, government law-breaking, or obscene inequality.

I can hear you trying to calm me down (I must be showing signs of another outburst). At least, you say, quite a lot of people have now woken up from their long slumber and seem to have made up their mind up not to vote Tory in future. Shouldn’t you be feeling optimistic at the prospect of a Labour government sometime next year? As other European countries move ever further to the right, shouldn’t we celebrate that Britain may soon move in the opposite direction?

Ah, I reply, but isn’t Britain already a long way down the road to political extremism of the right? And what is there to celebrate about the prospect of a Labour government? Keir Starmer says there’s ‘no money left’ to undo anything the Tories have done – exactly the reason George Osborne gave for his cuts – and nothing can be done until ‘growth’ produces more tax receipts. He’s abandoned all the policies he claimed to have before he became leader, and his vacuous ‘five missions’ amount to little. It’s hard to see that many people are going to see any substantial change with a Labour or Labour-dominated government. True, Tony Blair also threw many principles overboard before the 1997 election and, like Starmer, cosied up to Rupert Murdoch, but at least he had some policies to offer. Starmer seems to have none, and no settled principles. In effect, the Overton Window has moved a long way. While the Tories have become the equivalent of the US Republican Party, the UK Labour Party now occupies the ideological position of the previous Conservative Party.

I could go on, but I can feel the rage beginning to rise. So I’ll leave the politics and turn to the other possibility, that the fault is within me. I’ll concede at once that I’ve been a member of the Grumpy Old Men club for some years (bellowing at the TV is a well-known symptom). But the angry outbursts are more than grumps. And I don’t think senility or other mental problems have set in yet: I don’t get angry about other aspects of my life or the world around me.

But there’s one personal change that might account for the political fury. Time is beginning to run out if I’m going to have a chance of living in a fairer, kinder and more equal society than we have now. I’d like to think that I’ll see a time when public services are restored to health, water companies have ceased to poison our rivers, young people are treated with respect and given hope, children are no longer born into poverty, and better relations are re-established with neighbouring countries. And, above all, that the increase in inequality of wealth is reversed.

But I’m beginning to lose hope that I’ll live to see any of this. There doesn’t seem to be any political party or movement that might bring it about, especially given our undemocratic voting system. There seems no way out of the grim society we’ve allowed its worst members to create for us.

Yes, that’s it. That’s what’s changed. It’s the mounting despair that’s making me angry.

Leave a Reply