Long before all-year sea bathing became de rigueur with the middle classes of Mumbles, if you were up early enough, on any day of the week and at any time of the year, you’d be able to spot two figures in the waves on Caswell Bay. One of them was George Little. Born in 1927 on the ‘wrong’ side of the town, in Dan-y-graig, he became one of Swansea’s greatest lyric poets. His medium, though, was not words, but paint.

An earlier Swansea painter, William Grant Murray, once produced two large landscapes of the town, Swansea for pleasure and Swansea for business. The first took in the great sweep of the Bay to Mumbles, beyond the sunlit villas of Ffynone, while the other turned its eye towards the Eastside, the smoky world of copper works and coal docks, visible in the distance. In his work George wasn’t much interested in the pleasure zones of Swansea. His obsession was with the business of industry: the quaysides, terraced houses, railways and old industries of the lower Tawe valley. And rather than observing east Swansea from a safe distance, he preferred to get up close, to look with care, and even affection, at the chimneys, arches, brickwork and copper waste of the valley.

In large part this was work of the memory, not direct observation. The copper industry was already almost defunct, other industries were in steep decline, and few ships passed through the docks. In their place was dereliction. Before the Lower Swansea Valley Project started to sweep most of it away from the 1960s, the banks of the Tawe could boast one of the largest areas of industrial wasteland in Britain, mile upon mile of ruined works, isolated chimneys, spoil heaps and twisted metal. To George this was an irresistible subject. He knew it would not last, and he set about recording with his camera the old industrial world, in wide view and in close-up, before it vanished. Carolyn Little, his wife, has recently presented Swansea Museum with over a thousand of his photographs, an astonishingly rich archive of a disappeared city. George made use of the photos, and the preparatory studies he sketched, to produce what Peter Wakelin, in his new book on George Little, calls ‘beauty from the ugliest of matter’. The result was a large corpus of paintings and other works, stretching from the 1950s to 2017, in which colour, shape and construction transform objects of decay and desolation into intense visual pleasure.

There was a long history, of course, of artists being drawn to industry and its ‘ruin’d universes’, to use William Blake’s phrase. They often transmuted what they saw into visions of the sublime or ‘the sad grandeur of decay’, as in the later work of Turner and, more recently, of John Piper. But George, though connected to this romantic or neo-romantic tradition, was not himself part of it. His view was retrospective, but never nostalgic. As a young painter he was influenced by the expressionist work of Josef Herman, whom he knew, and the pale semi-surrealism of Eric Ravilious, but his mature style owed more to twentieth-century French painting, to the work of artists like Georges Braque, Fernand Leger and Robert Delaunay, who were absorbed by how to use bold colour and geometric forms in new ways. And to the painting of Carolyn, whose own work may have stimulated his shift towards the abstract (later they collaborated, ‘their styles and interests … deeply sympathetic’). In Britain, the artist who was closest, in subject matter and in artistic treatment, was Prunella Clough. George knew her, and quoted what she said about her own work, ‘it helps perhaps that so much of the industrial material is already abstract.’

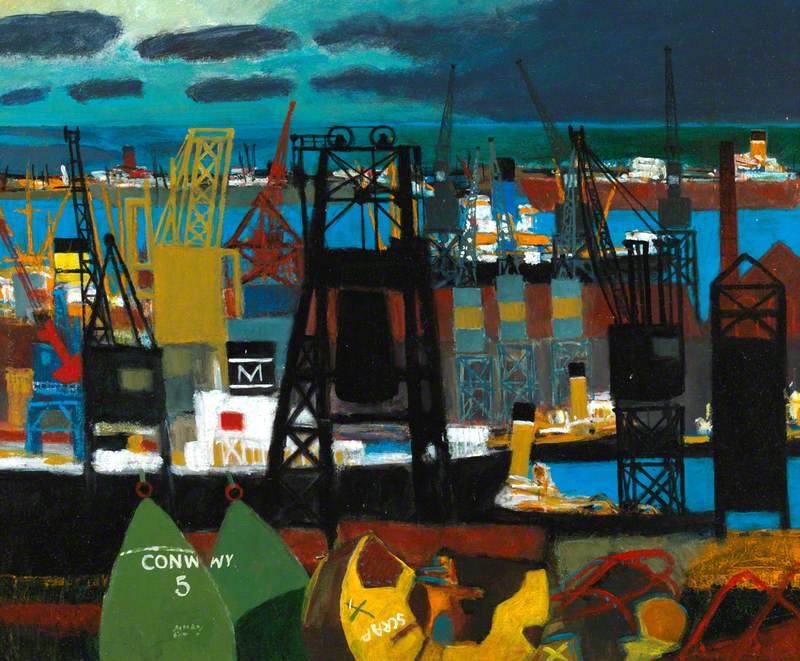

George’s concern for structure and abstraction, at their most intricate in his dockside scenes, with their funnels, cranes, coal hoists and buoys, might suggest a cool formalism. But most of his paintings are far from bloodless. The objects he paints may be inert fragments of industrial activity that long ago fell silent, but you often sense, when you stand in front of a picture of the Hafod copper work ruins, that the flames still burn and the sky is alive with their reflection. In an early street scene in Sheffield – George lived in south Yorkshire for five years – the city seems to be on fire, so vivid and lambent are the orange-red colours he uses. There’s a similar intensity in his late paintings recalling the Three Nights’ Blitz of Swansea in February 1941 (bombers destroyed Swansea Grammar School, which he attended, and he was evacuated to Mumbles). Yet George never lets feeling overrun form. Almost all his paintings are tightly and carefully shaped. It’s interesting that human figures rarely feature in them, and only occasionally in the photos.

George was an inspiring teacher of art. When I first knew him, he was on the staff of the Department of Adult Continuing Education in Swansea University. Earlier, he’d run the new Ceri Richards Gallery in Taliesin (now defunct), during one of the University’s rare bouts of interest in the visual arts. But his lasting legacies will be the vision of his art and the richness of his photographic archive.

Carolyn chose well in asking Peter Wakelin to prepare this book. He is one of Wales’s leading writers on art and artists of our age, and his background in industrial archaeology enables him to understand and interpret the scenes and objects in George’s works, so that he sees them almost through the same eyes as the artist. Parthian, the publisher, and Gwasg Gomer, the printer, have produced a book, handsomely designed by Olwen Fowler, that acts as a fine introduction to the work of George Little. At the end of the text Peter reproduces Bernard Mitchell’s photographic portrait of George, taken in 1998. He’s dressed in the same bright colours as his paintings, and to the fore are his large hands, plaited together and primed to work on the next painting. He’s an artist who deserves to be better known, well beyond his beloved Swansea and Wales.

Peter Wakelin’s book, George Little: the ugly lovely landscape (Cardigan: Parthian, 2023) was launched at Swansea Museum last Thursday. Peter and Prof. Prys Morgan, George’s old friend and fellow sea-bather, will be talking about George Little in the Tabernacle, Mumbles, on Thursday 16 November at 7:00pm.

Leave a Reply