These days librarians belong to a much-diminished profession (they’re not the only ones). But once you’ve become a librarian there are some things that stay with you for good. Among them is a commitment to the ideas of the collective provision of goods – as in ‘things that do good to people’ – and the ideal of public service. Public service, despite decades of privatising, outsourcing and disparagement, still survives in the minds and hearts of many. It would flourish again, if only some political party were brave enough to allow it to flourish.

The other thing that never leaves the long-time librarian is a primitive desire to bring order to the chaotic world of data and information, and help transmute them into knowledge. Primitive, and also largely redundant. Google and dozens of other commercial automated services long ago displaced mere people as a means of organising information, and new generations of AI applications now promise to trump Google – and in the process make several other knowledge-based professions redundant. Still, there are still some traditional areas where human orchestration of information survives. One of them is the indexing of books and other publications.

The printed book itself is a surprisingly healthy relic from the pre-digital age. Around 200,000 titles are published in the UK every year. A good proportion of them call for indexes to make them useful. So the book index, and the book indexer, have survived too.

I’ve been an indexer, on and off, since the 1970s. My biggest job was the first, a periodical index, covering over seventy years of publication, which took several years to complete. This was in pre-PC (personal computer) days. I’d write down each entry on a separate slip of paper, filing the slips in alphabetical order in a series of shoe-boxes at the end of each indexing session. As they grew in number, the boxes came to dominate the space in my tiny Cardiff bedsit. There wasn’t any intermediate typing stage. The slips went direct from Cardiff to Carmarthen, where Terry James, owner of his own letterpress Rampart Press, named after the outer edge of the old Roman fort of Moridunum, set and printed the index. The complete thing extended to 130 pages, and the effort to produce it exhausted both of us.

After that I became a ‘Sunday indexer’, taking on occasional jobs for friends and acquaintances who needed indexes done for their own books. These were easier to compile, and much quicker, once I became the owner of a PC. The first was an Amstrad PCW, a machine with a green screen and an aura of almost divine mystery and power (for all his many faults I’ve never been able to shake my admiration for Alan Sugar). Drusilla and Hilary Calvert had also released their program for book indexers, Macrex (it’s still available), which automated the slip-making and brought other benefits. I joined the Society of Indexers, collected a small library of books about indexing, and even wrote an article or two on the subject.

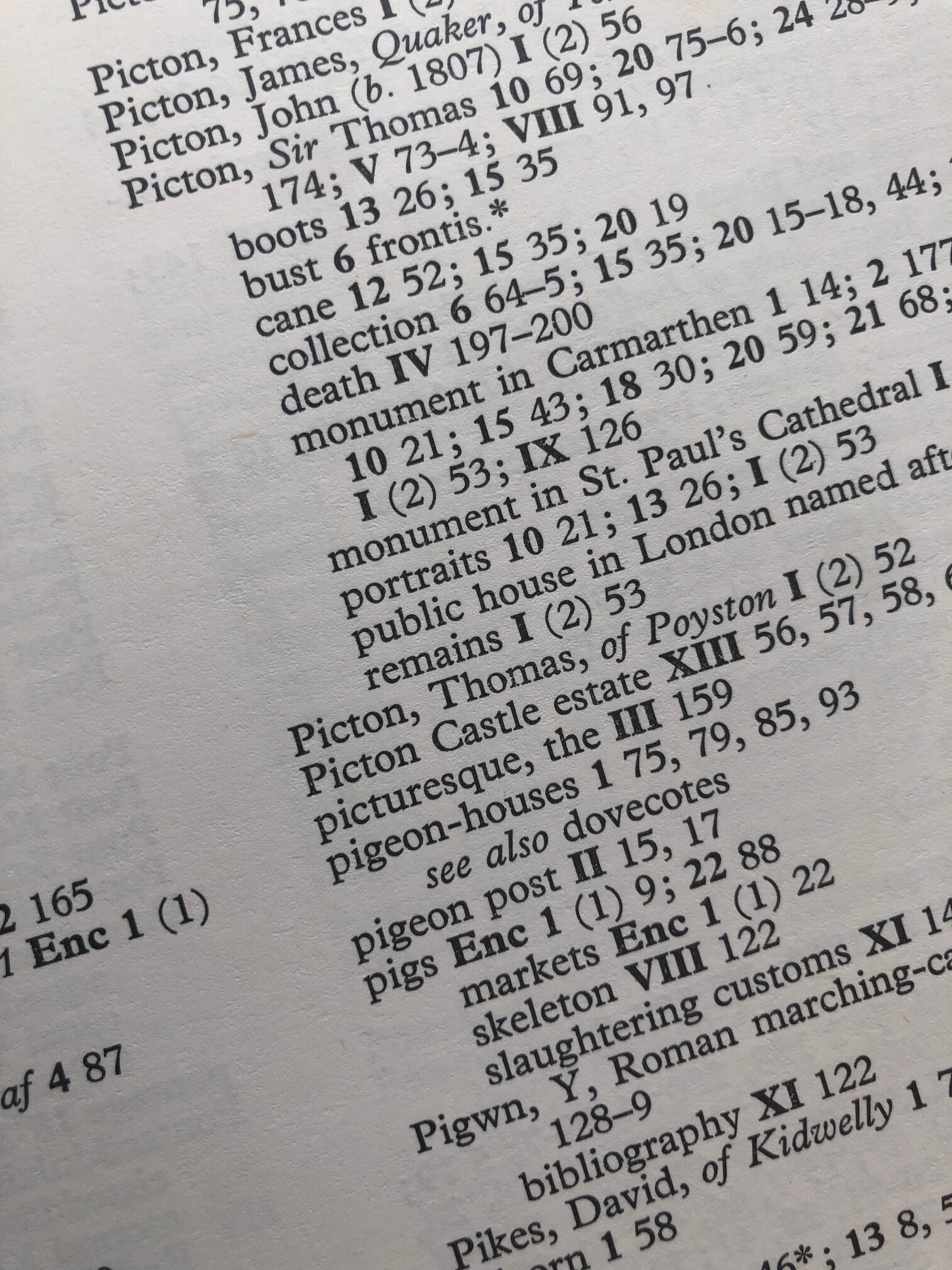

Then indexing took a back seat – until I found I needed indexes for my own books. Then I felt the old attraction returning. Filleting text for keywords and concepts, finding associations to be translated into cross-references, spotting errors in page proofs that the copy-editor had missed – all these operations I found strangely challenging and fulfilling. In fact, the old itch became so scratchy that I tacked on an index to Rhwng y silffoedd, a detective novel published in 2020 – possibly the first novel in Welsh to have one. Careful scrutiny of it also reveals the answer to the whodunnit, for those too impatient to read the text to the end.

I’ve spent most of the last three weeks putting together a new index, to a large, multi-author book. It’s been a bit of a slog. But I have to admit that it’s given me some of the old pleasure, especially knowing that the finished index will be essential for opening up the book to people who approach it for reference, rather than for all-through reading.

In time, no doubt, someone will devise an AI programme that will supersede the intellectual as well as the mechanical work of index-making. In the meantime, let’s celebrate the careful, dedicated and publicly-minded work of the human indexer.

Leave a Reply