By now the ‘invented tradition’ is itself a tradition. Since Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger published their edited collection The invention of tradition in 1983, we’ve become familiar with the idea that rituals, histories and beliefs that seem age-old were actually recent fictions devised with specific purposes in mind.

One of the chapters in The invention of tradition was contributed by Prys Morgan, who wrote about the rich array of cultural invention associated with Welsh nation-building in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A leading figure was Iolo Morganwg. Iolo invented any number of institutions, ceremonies and literary works as part of his mission to create the kind of ancient and contemporary Wales that he favoured. But Welsh cultural invention long pre-dated Iolo. An interesting example mentioned by Prys, one that proved equally useful to the Welsh and the English, originated in Wales over a century earlier. For convenience we’ll call it ‘The Last Bard’.

It’s possible that the tradition was slightly older, but it first appears as a brief, passing mention in Sir John Wynn’s The history of the Gwydir family, a manuscript written between 1580 and 1600 (it didn’t appear in print until 1770):

Edward the First, who caused all our bards to be hanged by martial law as stirrers of the people to sedition, whose example being followed by the governours of Wales, until the Henry the Fourth his time, was the utter destruction of that sort of men.

In fact there’s no evidence at all that Edward I, rapacious oppressor that he was, had Welsh poets put to death as a matter of policy. Wynn’s story is a fiction. Some scholars even think he’d made the story up himself to cover up the lack of poets in his own lineage. Its intention was presumably not just to intensify Edward’s ruthless suppression of all opposition, but also to paint him as intent on destroying the oral history and accumulated culture of the Welsh people. There may be an echo in the (historically attested) story of the slaughter of the Druids of Anglesey by the Roman army in 60CE.

Sarah Prescott has outlined how in Wales the ‘massacre of the bards’ myth developed a life of its own, as copies of Wynn’s work circulated in manuscript (one was available in the library at Mostyn). Evan Evans (‘Ieuan Fardd’), who did more than anyone else in the eighteenth century to collect and publish early Welsh poetry, repeated the story in the introduction to his pioneering anthology, Some specimens of the poetry of the ancient Welsh bards (1764). In his preface he writes of the poems he includes:

This is a noble treasure, and very rare to be met with; for Edward the First ordered all our Bards, and their works, to be destroyed, as is attested by Sir John Wynne of Gwydir, in the history he compiled of his ancestors at Carnarvon.

Evans was a strong Welsh patriot, intent on excavating his own cultural heritage for his own people. He printed the Welsh originals, his translations were prose versions, unadorned to suit English poetic taste, and he included a preface aimed at Welsh-speakers, ‘At y Cymry’. At the same time, he was also concerned in part to establish early Welsh poetry as an important, overlooked strand in the tapestry of the poetic tradition of Britain (by contrast he was sceptical of James Macpherson’s claims for ‘Ossian’, the supposed ‘primitive’ Scottish poet). Evans even included a long Latin ‘treatise on the bards’. This kind of practice is what modern scholars term ‘contributionism’, the anxiety of owners of a minority cultural tradition to have that tradition accepted by a larger, dominant culture. In both modes, as patriot and as educator, Evans wants to show that despite the oppressions of English rule symbolised by ‘massacre of the bards’, the works of the Welsh poets have survived destruction to live again in his own age.

Wynn’s invented tradition had already ‘jumped’ the border into England before Evans’s book appeared. In 1750 Thomas Carte published the second volume of a four-volume A general history of England, which includes this passage:

The onely set of men amongst the Welsh that had reason to complain of Edward’s soverignty were the Bards, who used to put those remains of the antient Britains in mind of the valiant deeds of their ancestors; he ordered them all to be hanged, as inciters of the people to sedition. Politicks in this point got the better of the king’s natural lenity: and those, who were afterwards entrusted with the government of the country, following his example, the profession became dangerous, gradually declined, and, in a little time, that sort of men was utterly destroyed.

This preserves the essence, and some of the wording, of Sir John Wynn’s story, though as an ‘Englishman’, which is how he describes himself on the title page, he takes a very different, stoutly Anglocentric view of Edward I and what he very generously calls his ‘natural lenity’. Thomas Percy noticed the passage and drew it to the attention of his friend, the poet Thomas Gray. Gray used it as the starting point of his remarkable poem ‘The bard’, published in 1757 (he doesn’t seem to have been aware of Evan Evans until later).

Gray is often regarded as a one-hit wonder, memorable only for his ‘Elegy in a country churchyard’, but in recent years critics have begun to look again at his small poetic output, especially for what it might tell us about Gray’s suppressed queerness. ‘The bard’ is a very different, and more perplexing, poem than the ‘Elegy’. A clue lies in its subtitle, ‘a Pindaric ode’. Many poets produced Pindaric odes at the end of the seventeenth and start of the eighteenth century, but ‘Pindaric’ for them meant little more than ‘free and rhapsodic’. Gray, a meticulous classical scholar, took the form much more seriously. The highly formal Greek poems of Pindar, who wrote in honour of successful athletes in Panhellenic festivals in the fifth century BCE, are notoriously difficult, being full of hinted-at references and sudden shifts of thought. Gray follows Pindar closely, in his poem’s structure (two pairs of triads – strophe, antistrophe and epode), and in its obscure, highly allusive content.

Contemporaries found ‘The bard’ difficulty to understand. Gray was persuaded, against his better instincts, to supply some explanatory notes. He wrote to Horace Walpole, who first printed the poem at his press at Strawberry Hill, ‘I do not love notes … they are signs of weakness and obscurity. If a thing cannot be understood without them, it had better not be understood at all’. The meaning of the Greek quotation from Pindar on the title page of his Odes is ‘speaking to the initiated’. (T.S. Eliot took much the same line with calls on him to add notes to ‘The waste land’, another highly allusive work, after its initial publication in 1922.)

Gray builds on the general ‘massacre of the bards’ theme by concentrating his poetic attention on one particular, unnamed bard, the last of his line. He also localises the scene on a crag in Eryri overlooking the river Conwy (an area unvisited by Gray himself at this time). And he adds a new element, not present in the original, the curse of the bard. Gray may have borrowed the motif from Tacitus’s account of the Anglesey Druids. This is how ‘The bard’ begins (the first strophe and antistrophe):

‘Ruin seize thee, ruthless King!

Confusion on thy banners wait,

Tho’ fann’d by Conquest’s crimson wing

They mock the air with idle state.

Helm, nor hauberk’s twisted mail,

Nor even thy virtues, tyrant, shall avail

To save thy secret soul from nightly fears,

From Cambria’s curse, from Cambria’s tears!’

Such were the sounds, that o’er the crested pride

Of the first Edward scatter’d wild dismay,

As down the steep of Snowdon’s shaggy side

He wound with toilsome march his long array.

Stout Glo’ster stood aghast in speechless trance;

To arms! cried Mortimer, and couch’d his quiv’ring lance.On a rock, whose haughty brow

Frowns o’er old Conway’s foaming flood,

Rob’d in the sable garb of woe,

With haggard eyes the poet stood;

(Loose his beard, and hoary hair

Stream’d, like a meteor, to the troubled air)

And with a master’s hand, and prophet’s fire,

Struck the deep sorrows of his lyre;

‘Hark, how each giant-oak, and desert cave,

Sighs to the torrent’s awful voice beneath!

O’er thee, O King! their hundred arms they wave,

Revenge on thee in hoarser murmurs breathe;

Vocal no more, since Cambria’s fatal day,

To high-born Hoel’s harp, or soft Llewellyn’s lay.

From this point the historical and literary allusions pile up fast. The Bard lists his fellow poets, already slaughtered by the invaders, ‘smear’d with gore, and ghastly pale’, while ravens and the eagle of Snowdon sail and scream overhead. Their ghosts assemble to take their revenge, and the Bard’s mourning now gives way to the chorus of the dead bards, prophesying retribution on Edward and the whole Plantagenet house. Each calamity is only hinted out, and you need Gray’s notes to keep up: Edward II (murdered at Berkeley), Edward III (predeceased by his son, the Black Prince, died abandoned), Richard II (starved to death), and so on. With the Tudors, though, comes renewed hope. With them the Welsh, or rather the ‘ancient Britons’, are restored to power, in accordance with Welsh prophecies. ‘Merlin and Taliessin had prophesied’, Gray says in a note, ‘that the Welch should regain their sovereignty over this island’. Poetry too is revived and blossoms anew. At the end the Bard returns to Edward I, assuring him that in the long expanse of time to come oppression is futile and poetry (and by extension civilization) will be triumphant:

Fond impious man, think’st thou, yon sanguine cloud,

Rais’d by thy breath, has quench’d the orb of day?

To-morrow he repairs the golden flood,

And warms the nations with redoubled ray.

‘Enough for me: with joy I see

The different doom our Fates assign.

Be thine Despair, and scept’red Care,

To triumph, and to die, are mine.’

He spoke, and headlong from the mountain’s height

Deep in the roaring tide he plung’d to endless night.

‘The bard’ inhabits two worlds simultaneously. One is the world of the island of Britain (or more narrowly, England). It traces the rupturing of tradition by oppressors, the ‘return’ of true Britons to power, and the survival of liberty and culture in the face of the oppression of unjust rulers. In his unpublished ‘Argument’ of the poem, Gray wrote that his message was that ‘all his [Edward’s] cruelty shall never extinguish the noble ardour of poetic genius in the island . . . and that men shall never be wanting … [to] boldly censure tyranny’.

The other world is Wales, the firm geographical focus of the poem. To Gray Wales offers a very different (and older) vision of poetry from the usual English model – or the current model of the poet as peripheral, commercial entertainer. Traditional Welsh society, he suggests, valued the poet more highly – as a critically important social and political actor, an oral guardian of culture, a leader of people and a powerful prophet.

‘The bard’ is a poem steeped in Wales. Gray had begun writing it in 1755, but found himself unable to complete it – until he heard the blind Welsh harpist John Parry play in a concert in Cambridge, where he lived. Afterwards he wrote to a friend, ‘Mr Parry, you must know, has set my Ode in motion again, and has brought it at last to a conclusion’. What had impressed him about Parry’s music was its apparent antiquity. Parry, he wrote, ‘scratch’d out such ravishing blind Harmony, such tunes of a thousand years old, with names enough to choak you, as have set all this learned body a-dancing’. Gray had also studied Welsh metrics – there are traces of cynghanedd at points in ‘The bard’ – and he later wrote five translations (‘imitations’) of Welsh poems selected from Evans’s collection.

The Welsh facets of ‘The bard’ were valued by later Welsh writers. Edward Jones wrote, in his Musical and poetical relicks of the Welsh bards (1784), ‘this lamentable event [the massacre of the bards] has given birth to one of the noblest Lyric compositions in the English language: a poem of such fire and beauty as to remove … our regret of the occasion, and to compensate for the loss.’ The response of Evan Evans was much more complicated. He wrote his own poem – in English, a rarity for him – in direct reply to Gray’s poem, entitled ‘A paraphrase of the 137th Psalm, alluding to the captivity and treatment of the Welsh bards by King Edward I’. Unlike Jones, Evans expresses a more assertive and resistant Welsh reaction to English oppression or assimilation. His captives refuse the request of the ‘Saxons’ to sing songs of joy, preferring to elegise the vanished court of Llywelyn. The poem ends:

On Conway’s banks, and Menai’s streams

The solitary bittern screams;

And, where was erst Llewelyn’s court,

Ill-omened birds and wolves resort.

There oft at midnight’s silent hour,

Near yon ivy-mantled tower,

By the glow-worm’s twinkling fire,

Tuning his romantic lyre,

Gray’s pale spectre seems to sing,

‘Ruin seize thee, ruthless King.’

In Wales the Last Bard as a theme extended beyond elite writers. In republican circles at the end of the eighteenth century, especially in London, he became a symbol for resistance to the repression and censorship of dissent by the Pitt government. In 1794 the radical Iolo Morganwg called Edward I a ‘bardicide’:

Edward the Bardicide, surnamed Longshanks, had caused many of the Bards to be massacred and all were severely restricted in the exercise of their ancient functions. They were Sons of Truth and Liberty, and of course offensive to that age of tyranny and superstition; but the Welsh would not suffer them to be exterminated.

In a letter of 1778 Iolo makes the connection with the present day even clearer: ‘We (the Bards of Glamorgan) have been as severely persecuted by Church and Kingists as our glorious predecessors were by Edward the Bardicide.’

At the Gwyneddigion Eisteddfod held at Denbigh in 1792 the set theme for the ode competition was ‘Cyflafan y beirdd trwy orchymyn Iorwerth y Cyntaf’ (the massacre of the bards by order of Edward I). Robert Williams of Eifionydd (Robert ap Gwilym Ddu) won the silver medal and published his poem in London. Another competitor was Evan Pritchard (‘Ieuan Lleyn’). At the 1798 eisteddfod a prize was awarded for the best translation of Gray’s poem. In 1822 William Owen Pughe published his Welsh translation of ‘The bard’, and in 1824, long after the ‘massacre’ story had been seriously doubted, William Owen wrote a prizewinning essay at the Cymreigyddion eisteddfod held at Caernarfon entitled ‘Hanes cyflafan neu ddinystr y beirdd Cymreig’ (the history of the massacre or destruction of the Welsh bards).

Gray’s Last Bard made a deep impression on writers. Indeed, ‘The bard’ could be regarded as the starting point for the fashion for ‘Celticism’ during the decades to follow. The poem also had an impact on visual artists. The setting, a bare rock among mountains above a river, and the central figure, a lone gaunt harpist, proved irresistible, in an age that was attuning itself to the appeal of the ‘sublime’ (Edmund Burke’s seminal treatise on the sublime was published in the same year as ‘The bard’). Gray himself was aware of the inherent visual power of the Bard. In a note on the lines describing his appearance, he wrote that the image ‘was taken from a well-known picture of Raphael [painted in 1518], representing the Supreme being in the vision of Ezekiel’. In another note he mentions another model, the picture of Moses in a painting by Parmigiano.

As F.I. McCarthy noticed, Horace Walpole, Gray’s printer, was keen to include illustrations with the 1757 Odes, and hired an artist called Richard Bentley to make sketches. Gray, though, disapproved of illustrations, and the sketches were abandoned.

The earliest visual work inspired by ‘The bard’ seems to be by Paul Sandby, the first eighteenth century English artist to devote sustained attention to the landscapes of Wales. In 1761, before he had set foot in Wales, he exhibited at the Society of Artists a painting he called ‘Historical landskip representing the Welsh Bard in the opening of Mr. Gray’s celebrated ode’. This work has not survived, but we have one contemporary reaction to it. William Mason, a poet friend of Gray’s, wrote breathlessly in a letter, ‘Sandby has made such a picture! Such a Bard! Such a headlong flood! Such a Snowdon! Such giant oaks! Such desert caves!’

The Bard’s image came back to Wales in 1774, when Thomas Jones of Pencerrig produced his large, uncharacteristically loud painting ‘The bard’. Today we may value his later paintings more highly, but he called it ‘one of the best I ever painted’. High in the (generalised) mountains – Jones had not visited Snowdonia – the Bard stands amid blasted trees. Sun from a ominous orange sky lights the scene, where the bodies of other poets lie dead on the ground. The barefoot Bard, equipped with ample white hair and beard, is wrapped in a long brown cloak. He walks towards his death at the edge of the precipice, but looks back, his right arm outstretched, at the approaching (unseen) English army.

In large part Jones follows Gray’s stage directions. His Bard is recognisable – ‘loose his beard and hoary hair / streamed, like a meteor, to the troubled air’ – and he carries his ‘lyre’. Ravens and an eagle fly above. There’s also a white bird flying off to the left. Could this possibly be a symbol of the undying spirit of the bards and their culture, a visual parallel to Gray’s final passage? But Jones makes one dramatic addition to Gray’s mountain furniture. In the middle distance is a miniature version of Stonehenge transplanted to Gwynedd. Jones, after a visit to the real Stonehenge, called it a ‘Stupendous Monument of remote Antiquity’. In his memoirs Jones performs a thought experiment with Stonehenge: ‘were this wonderful Mass situated amidst high rocks, lofty mountains, and hanging Woods – however it might contribute to the richness of the scene in general – would lose much of it’s own grandeur as a Single Object – The Experiment is easily tried upon Canvass’. His judgement may have been right.

This addition is a reminder of the habitual elision of the Bard and the Druid in visual art: since the mid-seventeenth century many had regarded Stonehenge as the work of the Druids, and in the eighteenth-century Wales, Anglesey in particular, developed something of what can only be called Druidmania. If Jones’s could be termed a ‘montane Druid’, he had a lowland counterpart, the ‘sylvan Druid’, as in ‘Solitude’, a large painting by Jones’s teacher Richard Wilson. Wilson’s Druid shares the loneliness of Jones’s, but is quite different in mood, being contemplative and depressive, rather than defiant and rhapsodic.

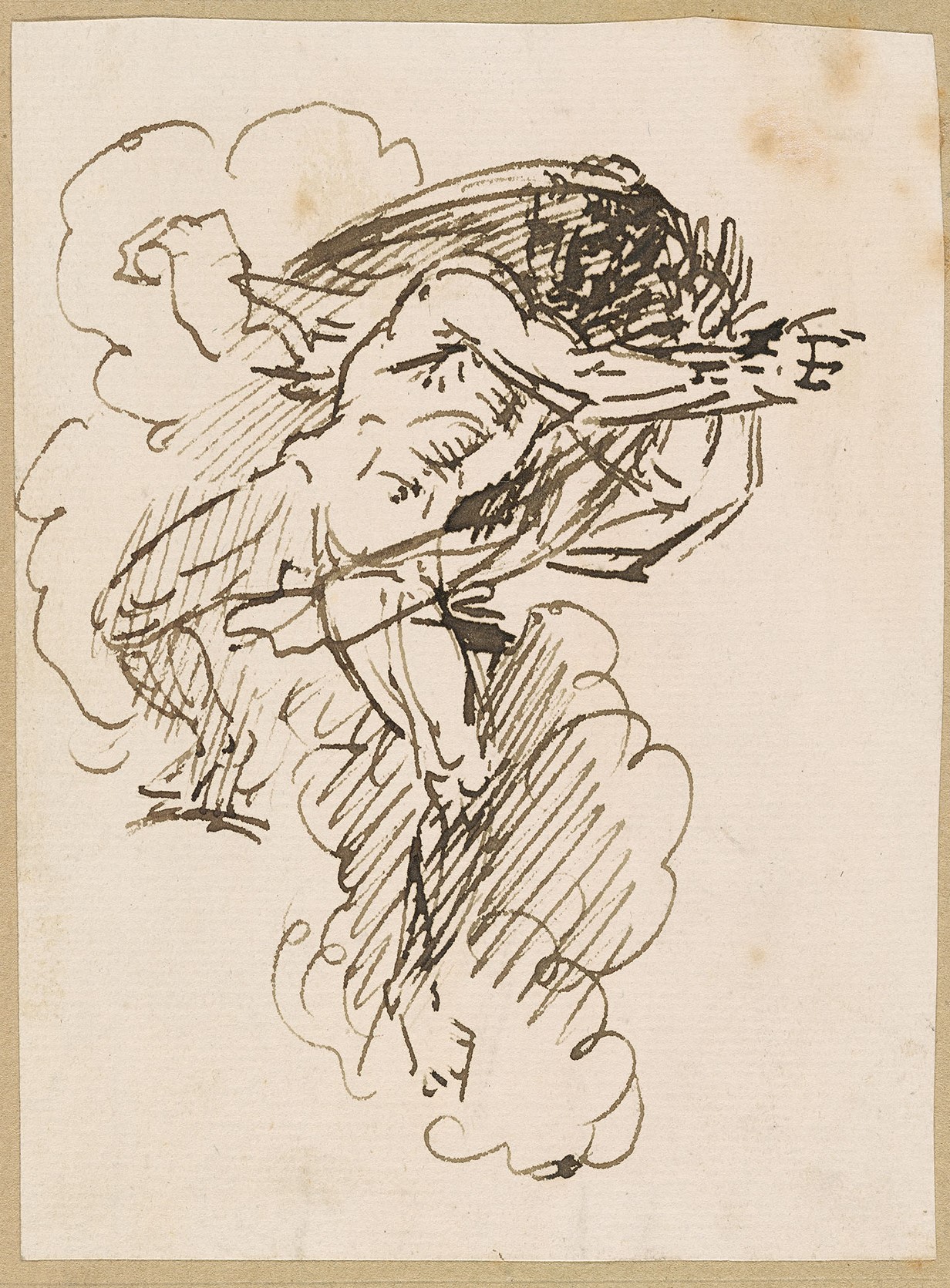

Soon the image of the Last Bard became a powerfully persistent motif on both sides of Offa’s Dyke. Four years after Jones’s picture the American artist Benjamin West tackled the same subject, but in a very different way. He banishes the mountain setting and fills his canvas with the statuesque, almost operatic figure of the Bard, dressed in a swirling black robe and holding his harp. (West’s energetic sketches for his painting offer a much livelier Bard.)

A now lost painting of 1784 by Philip James de Loutherbourg established a new, highly melodramatic variant, where the Bard teeters on the edge of a perilous rock above foaming waters, in a landscape more Alpine than Welsh. The picture became influential through being reproduced in prints, and being copied by other painters – for example, by John Harrison over fifty years later. A very early print formed the frontispiece of Edward Jones’s Musical and poetical relicks of the Welsh bards and so became fixed as an element of the public imagining of a medieval Welsh poet. The new dynamic Bard made his way back to Wales, as John Downman made a dramatic sketch of him and his lyre on the point of falling.

In 1797 William Blake was commissioned by John Flaxman to provide pen and watercolour illustrations to an edition of Thomas Gray’s poems published in 1790. His pictures appeared as frames surrounding individual pages of the original printed texts. The title page of ‘The bard’ could not be more different from De Loutherbourg’s. The Bard stands immobile alongside his huge (and improbably constructed) harp, closer to the ‘sylvan’ rather than the ‘montane’ type of Druid. The Bard was already a familiar Blake figure. He had painted a very similar figure, with the same harp, in his ‘The voice of the ancient bard’, originally a plate included in Songs of Innocence, but later moved to Songs of Experience. Rather than uttering curses, this Bard has a message of hope for the young (‘youth of delight’), that the ‘opening morn, image of truth new born’ will banish doubt, ‘clouds of reason’ and folly. Songs of Innocence begins with an instruction that begins with the stanza:

Hear the voice of the Bard!

Who Present, Past, & Future sees

Whose ears have heard,

The Holy Word,

That walk’d among the ancient trees.

One of Blake’s friends, Henri Fuseli, was similarly attracted to the supercharged emotionalism of Gray’s poem. His painting ‘The bard’, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1800, is lost, but a print gives some idea of the original. The extravagantly bearded Bard, perched high on a rock as in De Loutherbourg’s picture, hurls curses at the approaching horsemen.

At about the same time J.M.W. Turner was beginning – though he failed to complete it – a watercolour painting called ‘Looking down a deep valley towards Snowdon, with an army on the march’. Turner chooses a characteristically subtler, more oblique approach to the Bard. In fact, the Bard is nowhere to be seen. The landscape is everything. But snaking along the valley floor is a file of Edward’s soldiers on their mission of conquest.

No one could accuse John Martin of being subtle. The ne plus ultra of Last Bard pictures must surely be his apocalyptic, ‘shock and awe’ oil painting of around 1817. If the Bard was ever going to star in a Hollywood blockbuster, this is how he would appear. The composition is borrowed from De Loutherbourg. Dwarfed by a terrifying mountain landscape, the Bard flings his final curse, arm aloft, before throwing himself into the raging torrent far below. On the other bank of the river is the English army and – a Martin innovation – a Harlech-like Norman castle, symbolic of the foreign invader.

The Bard continued as a stock Welsh motif through the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth. He appears on Swansea pottery, in statuary, on medals and Eisteddfod costume designs. The ‘massacre of the bards’ theme did not survive so long, though it did make an unexpected cultural ‘jump’ into Hungarian literature. In 1857 János Arany, one of his country’s leading poets, wrote a work of passive resistance to Habsburg rule, an allegorical ballad about Edward I’s destruction of the bards, A walesi bárdok (The bards of Wales). The poem quickly became a central patriotic text for Hungarians intent on independence , and is still taught in Hungarian schools today. In 2007 in the National Library of Wales we received a donated copy of a new translation into English by Peter Zollman, in a memorable ceremony attended by staff of the Hungarian Embassy. The theme looped back from Hungary to Wales in 2010 when the Welsh composer Karl Jenkins wrote ’The bards of Wales’, a cantata for chorus, solo tenor and orchestra, using Zollman’s English translation and a Welsh translation by Twm Morys.

A walesi bárdok is the most surprising example of how the collective ‘false memory’ of the Last Bard and Edward I’s slaughter of the bards has evolved and mutated over a long period, crossing national boundaries on many occasions. To the Welsh the invented tradition supplied an attractive combination of defiance against political and cultural oppression and a defence of their own ancient and distinctive tradition of cultural leadership. For the English (or British), the Last Bard spoke of liberty, in this case, freedom from the authoritarian regimes of the European continent at a time when revolution and war threatened. And for Thomas Gray and perhaps others, the Bard pointed towards an alternative model of poetry that was deeply embedded in the political and social of its time – a model now out of reach of the socially peripheral writers and artists of Gray’s own day – and our own.

Leave a Reply