Urban is his element, and London his patch. But now, in his early seventies, Iain Sinclair has come home to his native Wales for his latest book, Black apples of Gower. For someone who’s followed the path of his wanderings and writings for years – I joined the trip late, with White Chappell, scarlet tracings in 1987 – it’s a surprise. By his own account Sinclair has avoided writing about Wales up to now, and on the face of it his people-centred exploring seems to have little in common with the rural earth-spirit school of Robert Macfarlane and others.

Urban is his element, and London his patch. But now, in his early seventies, Iain Sinclair has come home to his native Wales for his latest book, Black apples of Gower. For someone who’s followed the path of his wanderings and writings for years – I joined the trip late, with White Chappell, scarlet tracings in 1987 – it’s a surprise. By his own account Sinclair has avoided writing about Wales up to now, and on the face of it his people-centred exploring seems to have little in common with the rural earth-spirit school of Robert Macfarlane and others.

He doesn’t offer a complete explanation, but part of the answer may lie in the older man’s recursion to his youth – in this case to the caravan holidays he spend as a teenager at Horton, ‘a self-contained village on the edge of amnesia, situated at around the mid-point of Port Eynon Bay, on the southern ledge of the Gower Peninsula’. You have to add very quickly, though, that this is no uncomplicated homecoming. Within a couple of pages Sinclair dismisses any expectations of hiraeth quenched, ‘the genre of the Celtic return: the crumpled boyo skulking back to the shop-soiled plot of innocence’. A return journey to Gower, made with his wife Anna in September 2014, is underlain by memories, uncertainly substantiated by photos, postcards and other survivals, of his childhood visits, and of an intermediate trip, made with a friend, Brian Catling, in 1973. The trail west from Horton to Rhossili provides the main pilgrimage route on all three journeys. Each walk, accidentally on purpose, misses out its central destination, Goat’s Cave, the home of the Red Lady of Paviland, and it takes a supplementary trip, in March 2015, to track down the cave and, in the final chapter, to shadow the journey of its Palaeolithic resident to her/his current home in Oxford (where Catling makes a reappearance).

If Black apples of Gower has a thesis – and this is a much more organised text than it might seem to begin with – it’s the futility of a writer trying to ‘extract’ meaning from a landscape – any landscape, not just one remembered or misremembered from one’s past – by gathering factual or psychic evidence from its elements. Again and again Sinclair insists that what matters is not the author’s lending his exquisite consciousness to the land, but the opposite, a recognition of the land’s ability to be itself, unenhanced by the observer:

If Black apples of Gower has a thesis – and this is a much more organised text than it might seem to begin with – it’s the futility of a writer trying to ‘extract’ meaning from a landscape – any landscape, not just one remembered or misremembered from one’s past – by gathering factual or psychic evidence from its elements. Again and again Sinclair insists that what matters is not the author’s lending his exquisite consciousness to the land, but the opposite, a recognition of the land’s ability to be itself, unenhanced by the observer:

Terrain does not require the neurosis of language. We tie ourselves in such complicated knots trying to describe a thing that is all description. We confirm our own nuisance by employing, to greater or lesser effect, a redundant vocabulary of technical terms, overcooked epiphanies, showboating similes.

… place is poem. Identifying, like fully-paid up Romantics, some authentic wilderness, a rapture of gaze, is not our task. You don’t bring experience home like a souvenir. You listen and learn. You confirm. The walk does not require the walker.

Tramping off down the overgrown path towards the first headland was a gesture of initiation or reintegration with home territory. The Gower walk was my attempt at a ‘genetic interchange’ with salt, stone, plant, bird.

A ready example of Sinclair’s method on the Gower coast is to submit yourself to the de-scaling, alienating experience most walkers feel when they venture on to the coastal rocks under the cliffs at low tide,

… Carboniferous wave-cut limestone pavements: fractured, monochromatic. An alien planet revealed, submerged, revealed again. A lunar colony with no traces of past or future inhabitants. A terrain that is, simultaneously, before and after any whisper of civilisation.

The same emptied landscape struck the 1973 versions of Sinclair and Catling:

Catling played the last man on earth, or an unfortunate time-traveller catapulted into the Pleistocene. He hooks himself to the cliff face, musing on vanished grass and the total absence of plant or animal life. He could have crashed on an alien planet, or subsided into a J.G. Ballard pumice-desert brought about by climate change.

As always, Sinclair summons kindred, local spirits from the past to help him see with these post-Romantic spectacles. He starts with Dylan Thomas, but quickly lights on two other Swansea figures who took Thomas as their starting point but developed their own symbolic language for speaking about Gower, the poet Vernon Watkins and the artist Ceri Richards, ‘two quiet, determined men’. One chapter revolves round a visit Sinclair made to Watkins, also a Maesteg resident in his youth, in his Pennard home in 1961. It’s an appealing picture of the earnest, gauche youth and the kindly, oblique poet, propped up ill in his bed.

As always, Sinclair summons kindred, local spirits from the past to help him see with these post-Romantic spectacles. He starts with Dylan Thomas, but quickly lights on two other Swansea figures who took Thomas as their starting point but developed their own symbolic language for speaking about Gower, the poet Vernon Watkins and the artist Ceri Richards, ‘two quiet, determined men’. One chapter revolves round a visit Sinclair made to Watkins, also a Maesteg resident in his youth, in his Pennard home in 1961. It’s an appealing picture of the earnest, gauche youth and the kindly, oblique poet, propped up ill in his bed.

Adequately swotted up for the Dylan Thomas part of my interview, I was underprepared for conversation with Vernon Watkins … [His recollection of a youthful trip to see Yeats in Dublin] was gracefully done, making it clear that the nuisance of young men knocking on the doors of established poets was an honourable tradition.

A photograph of Watkins at work behind his desk in Lloyds Bank in St Helen’s Road, Swansea calls up an acutely detailed analysis of the poet within his three-piece suit. For Sinclair he represents the ideal of a poet in his landscape: ‘… a willed abnegation of originality. A wearing away of egoic interference. A oneness with the indifferent gods of rock and wave.’ It’s interesting that Vernon Watkins, for all his modesty, seems to have exerted a powerful influence on young writers – Philip Larkin was another.

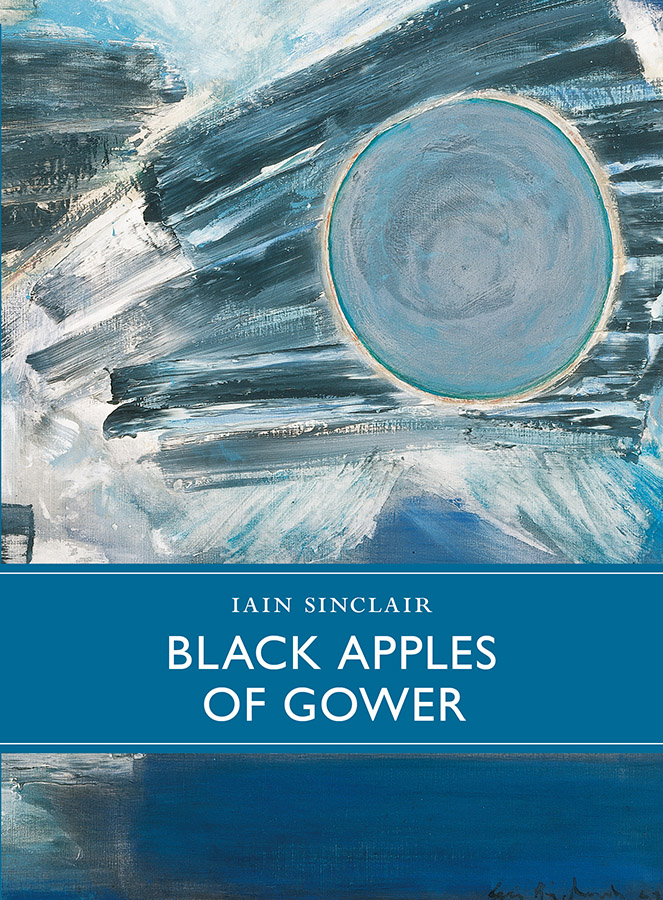

Ceri Richards’s work was also already known to the young Sinclair, who owned a copy of the startling lithograph ‘Do not go gentle into that good night’. Here he focusses on the drawings Richards made, ‘in a state of fugue’, on printed copies of Dylan Thomas’s Collected poems, by uncanny coincidence just hours before Thomas’s death in New York. The full-page drawing ‘illustrating’ the stanza beginning ‘I dreamed my genesis in sweat of death’ shows a length of Gower cliffs, in which are hidden an owl and other creatures. Blasted into the centre of the scene is a black roundel, a mandala or mechanical drill, the ‘black apple of Gower’. Inside it, an organic Celtic triskele pattern, ‘sexual, suspended between fixed identities, male and female, testis and ovary’.

Ceri Richards’s work was also already known to the young Sinclair, who owned a copy of the startling lithograph ‘Do not go gentle into that good night’. Here he focusses on the drawings Richards made, ‘in a state of fugue’, on printed copies of Dylan Thomas’s Collected poems, by uncanny coincidence just hours before Thomas’s death in New York. The full-page drawing ‘illustrating’ the stanza beginning ‘I dreamed my genesis in sweat of death’ shows a length of Gower cliffs, in which are hidden an owl and other creatures. Blasted into the centre of the scene is a black roundel, a mandala or mechanical drill, the ‘black apple of Gower’. Inside it, an organic Celtic triskele pattern, ‘sexual, suspended between fixed identities, male and female, testis and ovary’.

Other Sinclair regulars, like William Blake, Alan Moore, John Clare and Geoffrey Hill, invite themselves along on the trip, despite their lack of Gower credentials, and we’re treated to numerous digressions that will intrigue non-Welsh readers, like the terrifying Mari Lwyd (active in Llangynwyd, close to Sinclair’s Maesteg birthplace; Sinclair reveals he once prepared a television adaptation of Watkins’s ‘Ballad of the Mari Lwyd’), William Price, Llantrisant (his cremationist enthusiasm paralleled with the cremation of Sinclair’s parents at Margam), and the sand-drowned village of Kenfig. A final deviation leaves us stranded, for no particular reason, in the Oxfordshire countryside, where the book rather peters out. But not before its real climax, the successful location of Goat’s Cave, helped by a mysterious ‘woman in blue’, and a trip to the Oxford University Museum of Natural History to commemorate the extraordinary creationist, coprophile and extreme carnivore, Dean William Buckland. It was he who in effect kidnapped the Red Lady – the Paviland finds were originally made by Swansea locals. The half-a-skeleton of the Lady – or rather a replica of it – now stands, strung up and disarticulate in a glass case in the Museum, to Sinclair’s dismay: ‘Buckland’s theft undid the power of the original chamber’.

Black apples of Gower, for all its disavowal of romanticism, has its full share of its author’s customary rhapsodic style. But, as usual, Sinclair the satirist modifies Sinclair the magus. The mythic black apple is prefigured by the green and red Big Apple in Bracelet Bay. Gower’s economy depends not so much on tourism as on the collection of car parking fees. The path between Rhossili and Worm’s Head, to Sinclair’s surprise and horror, is thronged with Asian tourists (‘I thought I was hallucinating a touring production of Miss Saigon‘), each armed with a selfie stick (‘a small camera fixed on a wand, so that intertwined lovers could star in their own movie’).

Black apples of Gower, for all its disavowal of romanticism, has its full share of its author’s customary rhapsodic style. But, as usual, Sinclair the satirist modifies Sinclair the magus. The mythic black apple is prefigured by the green and red Big Apple in Bracelet Bay. Gower’s economy depends not so much on tourism as on the collection of car parking fees. The path between Rhossili and Worm’s Head, to Sinclair’s surprise and horror, is thronged with Asian tourists (‘I thought I was hallucinating a touring production of Miss Saigon‘), each armed with a selfie stick (‘a small camera fixed on a wand, so that intertwined lovers could star in their own movie’).

Sinclair’s research is thorough – although it’s curious that, as a people-in-their-landscape geographer, he neglects to record any interactions with the natives. The only regrettable omission from his bibliography is Nigel Jenkins’s Real Gower – a pity, since Nigel was a remembrancer who belonged to the Sinclairian tradition and knew Gower and its people intimately, man and boy.

This book is a treat. Not just for the text, but as a physical object. It has, among other things: a medium size and chunky shape; a firm binding, with headband (not that common these days) and well-designed jacket; thickish white paper of good quality; an elegant and readable serif font. It also has a wealth of illustrations, mostly grainy black and whites à la Sebald, though others are in colour, including some stunning reproductions of Ceri Richards paintings, by permission of his family. All this for £15. The publishers are Little Toller Books, of Toller Fratrum, Dorset. They made their name through handsome reprints of rural classics, but they also produce new works, especially in their Monographs series, of which this is number 5. I strongly advise purchase, if you enjoy reading Iain Sinclair, or just like having good books – but buy direct from the publisher, not through Amazon.

Leave a Reply