From my early childhood, an evening mug of hot chocolate has been a small but constant source of comfort. I suspect it’s a common addiction. Chocolate drinking is not a failing that many grown-up people own up to, and certainly not one that many would think of writing about. A notable exception is the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins.

I’ve been reading some of Hopkins’s journals. He never intended anyone else to see them, and they contain many passages of observation that would not have met with the approval of the stern clerics who ruled his life from the age of 22. There are few more extreme cases than Hopkins of someone who self-imprisoned a hypersensitive imagination and deeply repressed sexual feelings. After converting to Catholicism in 1866 he submitted himself to the doctrinal tyranny of the Jesuits. They damned and outlawed the free interpenetration of mind, eye and feeling that came so naturally to Hopkins the poet. In 1868 he destroyed all the poems he’d written so far, and vowed never to write more.

In the journals, though, the poet survives, especially in his descriptions of the natural world that make up many of the entries. They share two constants. One is an intense concentration on the things Hopkins observed – often very small and overlooked things: in his famous words, ‘all things counter, original, spare, strange’. The other is a free, elated flow of words –words that fail to obey normal rules and prefigure the revolutionary poems of his years in Wales.

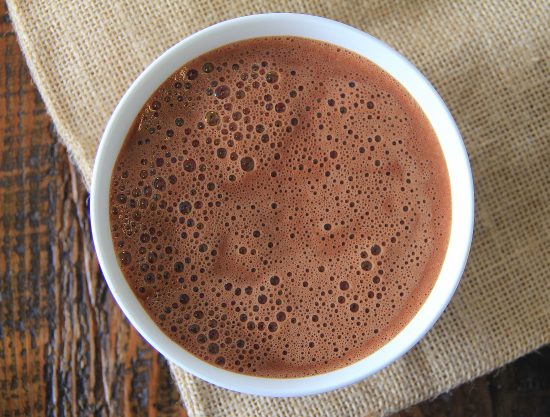

The entry that includes hot chocolate is undated, but was written sometime in the first half of March 1871, when Hopkins was living at Stoneyhurst, the Jesuit college in Lancashire, part-way through his immensely long training to be a priest. This is how it begins (‘Lenten chocolate’: the novitiates were allowed hot chocolate only occasionally, it seems, as a treat during Lent):

The spring weather began with March about I have been watching clouds this spring and evaporation, for instance over our Lenten chocolate. It seems as if the heat by aestus [surge], throes/ one after another threw films of vapour off as boiling water throws off steam under films of water, that is bubbles. One query then is whether these films contain gas or no. The film seems to be set with tiny bubbles which gives it a grey and grained look. By throes perhaps which represent the moments at which the evener stress of the heat has overcome the resistance of the surface or of the whole liquid. It would be reasonable then to consider the films as the shell of gas-bubbles and the grain on them as a network of bubbles condensed by the air as the gas rises. — Candle smoke goes by just the same laws, the visible film being here of unconsumed substance, not hollow bubbles The throes can be perceived/ like the thrills of a candle in the socket: this is precisely to reech whence reek. They may by a breath of air be laid again and then shew like grey wisps on the surface — which shews their part-solidity. They seem to be drawn off the chocolate as you might take up a napkin between your fingers that covered something, not so much from here or there as from the whole surface at one reech, so that the film is perceived at the edges and makes in fact collar or ring just within the walls all round the cup; it then draws together in a cowl like a candleflame but not regularly or without a break: the question is why. Perhaps in perfect stillness it would not but the air breathing it aside entangles it with itself. The films seems to rise not quite simultaneously but to peel off as if you were tearing cloth; then giving an end forward like the corner of a handkerchief and beginning to coil it makes a long wavy hose you may sometimes look down, as a ribbon or a carpenter’s shaving may be made to do.

Hopkins was no physicist, but his scrutiny of the surface of the hot chocolate is almost scientific in its concentration and questioning. He wants to know what’s really happening as he watches the skin of the chocolate change. At the same time, still the poet, he’s constantly turning to metaphor as an aid to understanding: the candle and its smoke, the fingers drawing up a napkin, the tearing of cloth, the long wavy hose. Anything to help him uncover the secret of movement and pattern in nature. Ben Belitt notes that this passage reads, aloud, as a meditative soliloquy, with a specialist vocabulary: ‘the permutations of energy, as Hopkins summons them up, are at once Protean and fanciful: we see water as vapor, steam, bubbles, gasses, films, throes, shells, grains, thrills, wisps, collars, rings, hoses, ribbons, shavings, frets, coils, etc.’

The journal entry continues without a break. But we realise that Hopkins has now moved on, from chocolate to clouds:

Higher running into frets and silvering in the sun with the endless coiling, the soft bound of the general motion and yet the side lurches sliding into some particular pitch it makes a baffling and charming sight. — Clouds however solid they may look far off are I think wholly made of film in the sheet or in the tuft. The bright woolpacks that pelt before a gale in a clear sky are in the tuft and you can see the wind unravelling and rending them finer than any sponge till within one easy reach overhead they are morselled to nothing and consumed — it depends of course on their size. Possibly each tuft in forepitch [=?projection: a Hopkins coinage] or in origin is quained [=made angular: another unique Hopkins word] and a crystal. Rarer and wilder packs have sometimes film in the sheet, which may be caught as it turns on the edge of the cloud like an outlying eyebrow. The one in which I saw this was in a north-east wind, solid but not crisp, white like the white of egg, and bloated-looking What you look hard at seems to look hard at you, hence the true and the false instress of nature.

If the chocolate brings out the scientific observer in Hopkins, clouds provoke the poet in him. His language suddenly takes off. Visual images are no longer enough: the clouds become vividly tactile. The metaphors multiply. New-minted words are pressed into service.

The passage ends:

One day early in March when long streamers were rising from over Kemble End one large flake loop-shaped, not a streamer but belonging to the string, moving too slowly to be seen, seemed to cap and fill the zenith with a white shire of cloud. I looked long up at it till the tall height and the beauty of the scaping — regularly curled knots springing if I remember from fine stems, like foliation in wood or stone — had strongly grown on me. It changed beautiful changes, growing more into ribs and one stretch of running into branching like coral. Unless you refresh the mind from time to time you cannot always remember or believe how deep the inscape in things is.

‘Inscape’, another invented word, is one of Hopkins’s key ideas. When applied to an aspect of the natural world, like a cloud, it refers to the essential structure or principle that lies behind the ever-shifting surface: its distinctiveness or individuality, or what his favourite philosopher, Duns Scotus, called ‘haeccitas’ or ‘thisness’. ‘Instress’, used earlier in the passage, is the thread of tensions and movements that holds the inscape together – and something more: the sensation and impact of the thing on the perceiver. So, the perceiver and the thing perceived interact; hence, ‘What you look hard at seems to look hard at you, hence the true and the false instress of nature.’ In another journal entry, on 12 December 1872, Hopkins observes, when walking with a friend on the Lancashire fells, ‘green-white tufts of long bleached grass’ and writes, ‘I saw the inscape … freshly, as if my eye were still growing, though with a companion the eye and the ear are for the most part shut and instress cannot come.’

Time and again, images from the natural observations of the journals lie dormant in Hopkins’s mind and find their way years later, in Wales and later, into the mature poems. Distinctive and rare Hopkins words are mined, and placed in new settings. In ‘Penmaen Pool’, the word ‘tuft’ reappears, transposed from clouds to snow:

Then even in weariest wintry hour

Of New Year’s month or surly Yule

Furred snows, charged tuft above tuft, tower

From darksome darksome Penmaen Pool.

In the extravagant late poem, ‘That nature is a Heraclitean fire’, tufts are returned to the sky:

Cloud-puffball, torn tufts, tossed | pillows flaunt forth, then chevy on an air-

built thoroughfare: heaven-roysterers in gay-gangs | they throng; they glitter in marches.

Likewise, ‘morselled’ returns, in ‘Andromeda’, moved from the physical to the emotional realm:

All while her patience, morselled into pangs,

Mounts; then to alight disarming, no one dreams,

With Gorgon’s gear and barebill, thongs and fangs.

And even ‘quain’ is remembered in the late poem ‘Epithalamion’:

Till walk the world he can with bare his feet

And come where lies a coffer, burly all of blocks

Built of chancequarrièd, selfquainèd rocks

It seems, alas, that Hopkins never got round to finding a poetic counterpart for the journal’s cup of hot chocolate or its grey, grained film of bubbles. It’s sad that hot chocolate inspires poets so rarely. Its cousin, cocoa, has been luckier. It made the name of Wendy Cope in 1986 when she published her first collection, Making cocoa for Kingsley Amis. The enigmatic title poem goes like this:

It was a dream I had last week

And some kind of record seemed vital.

I knew it wouldn’t be much of a poem

But I love the title.

Leave a Reply