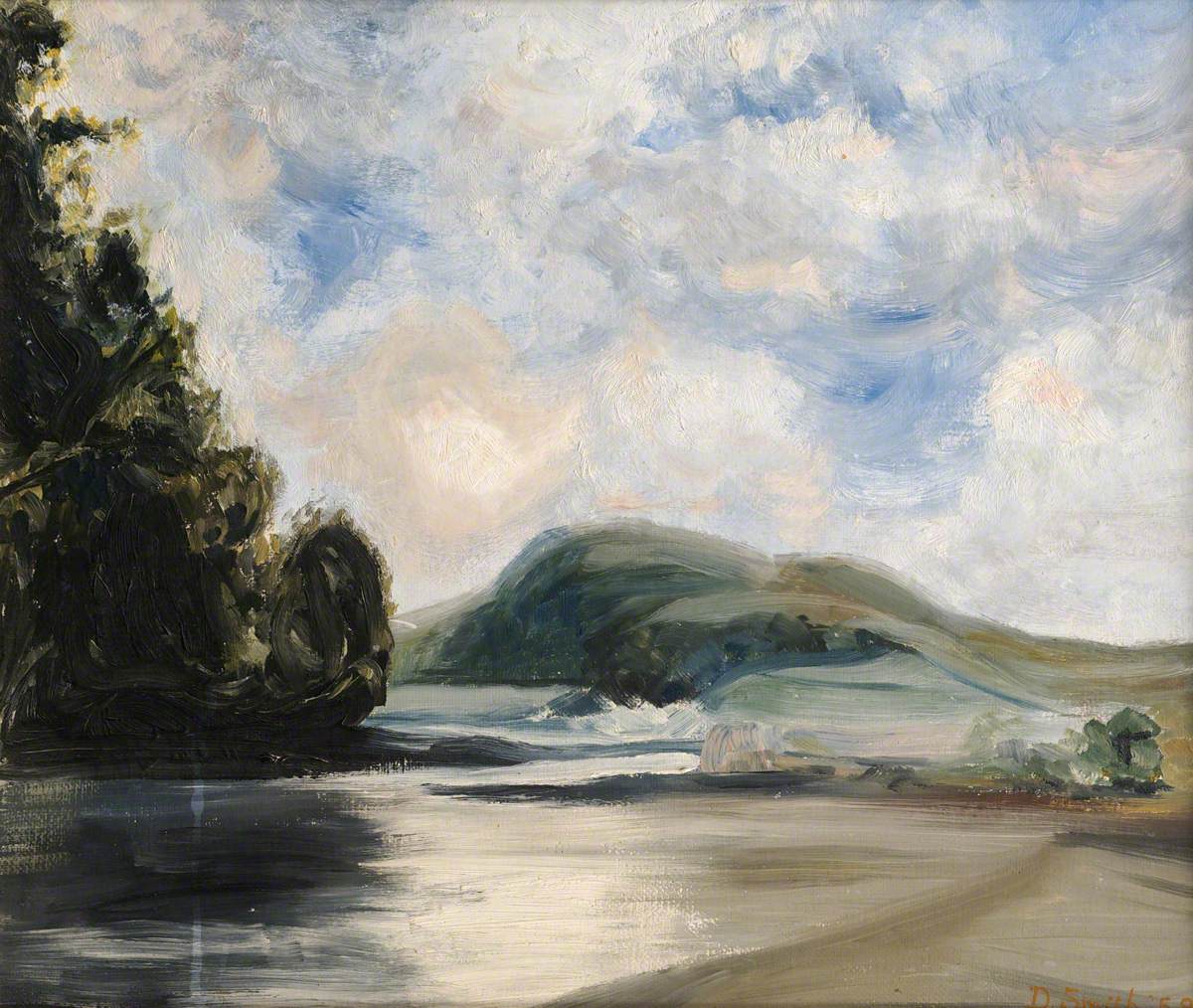

This small corner of Carmarthenshire is new to me – the point where the Cothi flows into the Tywi, just west of Llanegwad. A track leaves the village, passes a cottage, Penygoilan, and a farm, Llwchgwyn, and then turns into a narrow lane that leads down to the banks of the Tywi and a large eighteenth century farmhouse, Abercothi Farm (another, Victorian building, Abercothi House, sits on a hillside, across a broad lawn, to the north).

At the beginning of the eighteenth century Abercothi, or an earlier version of it, belonged to an intriguing man named Erasmus Lewis. There’s a tradition that he was born there, in 1670, but, according to Prys Morgan, it seems his father, George Lewis, vicar of Abergwili, acquired the house around 1700. Erasmus was sent by his wealthy father on a scholarship to Westminster School, and entered Trinity College, Cambridge as a pensioner (fee-payer) in 1590. This education seems to have given him the right connections, because after graduating he went to Berlin, from where he sent regular ‘newsletters’ to John Ellis, an under-secretary of state in the Tory government. After several moves round Europe he settled in Paris and became secretary to Charles Montagu, Earl of Manchester, the English ambassador to France. Montague lost his job in 1701, and Erasmus eventually returned to his home county, where he seems to have become a schoolteacher for a time.

In 1704 he found another aristocratic political patron, Robert Harley, who employed him as his ‘under-secretary’. Harley was acutely aware of the benefits of political spin, and employed Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Swift and others to make sure his point of view was understood. Erasmus had another spell abroad, in Brussels, and continued to work for government ministers until 1714, when Harley was toppled after the Hanoverian takeover. Erasmus seems to have developed a reputation for inscrutability and lack of feeling. Harley said he had ‘not the soul of a chicken nor the heart of a mite.’

What exactly was Erasmus Lewis doing all this time? The Oxford dictionary of national biography describes him as a ‘government official’, but that sounds anachronistic: party politics and the machinery of government were still in their infancy. In reality, he may have been the equivalent of a ‘Spad’, a special adviser, or fixer, spin-doctor and gofer for his various Tory bosses – in effect, an early Dominic Cummings. There’s another possibility, suggested by his trips abroad, his ‘newsletters’ and his curious ‘retirement’ to Carmarthen after 1701: that he was also a spy, employed to nose around his contacts in foreign governments and report back useful intelligence to his controllers. John Le Carré’s ‘Circus’ lay in the far future, but organised espionage already had a long history in Europe (the playwright Christopher Marlowe was probably one a hundred years earlier).

Between 1712 and 1713 Erasmus was ‘Provost Marshal’ for the slave colony of Barbados, but was content to avoid going there. In 1713 he was elected as MP for Lostwithiel in Cornwall, but stayed only until 1715. He married Anne Bateman in 1724, but little more is heard of his career before his death aged 83 in 1754. He was buried, with his wife, in the east cloister of Westminster Abbey.

There was another, literary side to Erasmus. His patron Harley was a patron and friend of many of the leading writers of the day, and Erasmus got to know them, including Alexander Pope, John Gay, Matthew Prior and Jonathan Swift. In a poem Swift wrote, ‘this Lewis is an arrant shaver, and very much in Harley’s favour’. But he was grateful to Erasmus for introducing him to Harley, and he and Erasmus became friends. In 1713 Swift defended him from false accusations that he favoured the Jacobites, in an article later reprinted as A complete refutation of the falsehoods alleged against Erasmus Lewis, esq. Swift denounced the rumours as ‘a monstrous story [that] has been for a while most industriously handed about, reflecting upon a gentleman in great trust under the principal secretary of state.’ In April 1727 Swift sent a letter to his publisher Benjamin Motte, under the pseudonym ‘Richard Sympson’, to say that Erasmus could negotiate on his behalf a secret contract to publish ‘my cousin Gulliver’s book’ – the second edition of Gulliver’s travels.

He never seems to have lived there again, but back in Carmarthenshire Erasmus was busy collecting and disposing of estates. From his father he inherited Abercothi and land in Newchurch, north of Carmarthen, both of which he later sold, and he added more estates, including Allt-y-gog and land in Gower. These shrewd dealings meant that at the time of his death he was worth over seven thousand pounds.

No portrait has survived of Erasmus Lewis – spads and spies usually prefer to be inconspicuous – so we have to imagine how he might have looked: a thin figure (water was his favourite tipple), long wig, evasive eyes, and maybe an expression of discreet satisfaction that a young Carmarthenshire crwt had transformed himself into a powerful Tory fixer at the heart of government.

Leave a Reply