It’s a commonplace that since George Osborne set in motion the immiseration of poor people, through his programme of austerity and big cuts in benefits, Britain has seemed to regress to the time of our Victorian ancestors. ‘Poor laws’, and the nineteenth century distinction between deserving and undeserving poor, are back with us, and so too is the practice of paying many employees so little that they cannot survive on their wages alone. Since Osborne’s time there’s been no let up in the process. There are now more food banks than there are branches of McDonalds, and they’re used by over 2.5m million people.

But in another area, standards of political behaviour in government, you could now argue that under Boris Johnson we’ve retreated even further into history, to the pre-democratic eighteenth century. Lying, favouritism, corruption, illegality, threats and all the other regular habits of Johnson and his fellow-gangsters are more similar to the political culture of that era than to the Victorians. For all their faults, Gladstone, Disraeli and their contemporaries shared a belief that those in power had a serious duty to serve the people rather than simply get their own way, irrespective of the law or the interests of others, and enrich themselves and their friends. Charles Trevelyan, for example, was largely responsible for pioneering the reform of the civil service, so that accountability replaced favouritism and public service replaced party allegiance.

In the first half of the eighteenth-century things were different. National politics was dominated by gangs, mainly Tories and Whigs, who fought each other for power with scant regard for morality or the interests of others. The dominant figure of the time was Sir Robert Walpole, generally regarded as the first Prime Minister. It’s Walpole, rather than his hero Winston Churchill, who most closely resembles Boris Johnson in his behaviour. (Admittedly Walpole’s dominance lasted for twenty years, rather longer than Johnson is likely to survive.)

Like Johnson, Walpole was educated at Eton College, where his power networking no doubt began. He turned to politics and found a pocket borough, King’s Lynn, to elect him as MP. Like Johnson, he was a chancer: he invested in what became known as the South Sea Bubble, selling his stock before the bubble burst (he protected government ministers accused of corruption on the scheme). As Johnson became ‘Boris’, Walpole was known by all as ‘Robin’ – though the word’s connection with robbery always surrounded his regime, satirised as the ‘Robinocracy’. In 1712 he was convicted by Parliament of ‘a high breach of trust and notorious corruption’ following the letting of contracts in Scotland, was locked in the Tower for six months, and barred from the House of Commons. In 1714, when George I came to the throne, the Whigs had begun their 50-year ascendancy, and Walpole’s rise accelerated. By 1721 he was in effect Prime Minister, and gathered enormous power to himself.

Walpole used every kind of machination to survive and prosper. He removed rivals from his cabinet, gave himself and his sons titles, and, even when unpopular in the country, took ruthless advantage of his large majority in the Commons. He was notorious for his bribery, corruption and favouritism, which his supporters defended on the grounds that these vices were grounded in basic human nature. He amassed a personal fortune, part of which he used to build a large gallery of old master paintings in his extravagant new house in Norfolk, Houghton Hall.

Walpole, for all his unchallenged power, was not without his enemies. The official political opposition may have been ineffective, but in the world of print, at least, there were many forceful voices raised against the regime. John Gay, Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope and Henry Fielding were just a few of the writers directing often vicious satire towards Walpole and his cronies. Then there were the cartoonists: this was the period that saw the rise of the political cartoon. Many cartoonists were unsparing in their attacks, and some of their productions bear a striking likeness to those produced by the more visceral cartoonists of the Johnson era, like Steve Bell, Martin Rowson and Cold War Steve.

To take one example, here’s an anonymous cartoon published in 1740, towards the end of Walpole’s long career. Entitled Idol-worship or The way to preferment, it offers a graphic and literal picture of political arse-licking. In St James’s Palace a gargantuan Walpole, breeches down, bares his backside to a diminutive gentleman, who pays flattering attention to it. Another sycophant rolls a hoop between the giant’s legs; the hoop lists Walpole’s many attributes: pride, vanity, folly, luxury, and so on.

Denuding Boris Johnson is a common tactic used by some of our own cartoonists to reveal his ugliness and coarseness, and his lack of political substance. Like his eighteenth-century predecessor, Steve Bell exposes the prime minister’s buttocks, which regularly appear where Johnson’s face should be. Each successive cartoon reignites the reader’s disgust.

Cold War Steve uses the same approach. A fleshy, naked Johnson prances gleefully through his collages, surrounded by scenes of misery and despair borrowed from antique paintings. Disgust here extends to revulsion at Johnson’s unconcern for the interests of anyone but himself.

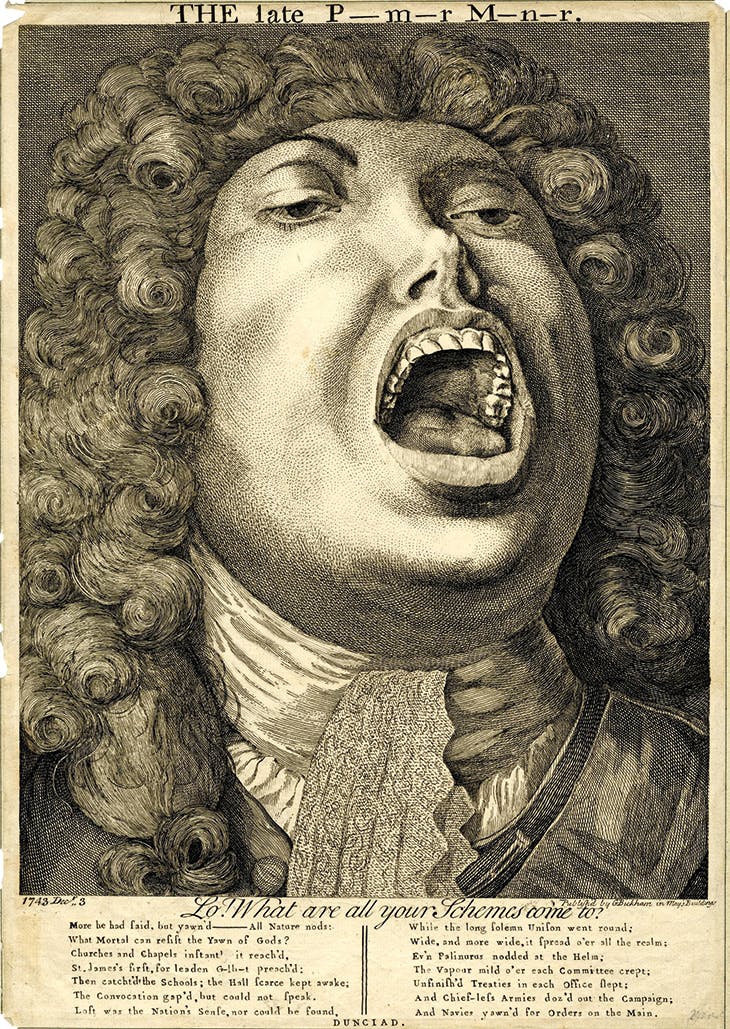

In 1743, after Walpole at last fell from power, George Bickham the Younger produced a cartoon entitled ‘The late P – m – r M – n- r’. Walpole, bewigged, and double-chinned like our own Tory MPs, tosses back his fleshy head and opens his mouth in a giant yawn: the epitome of complacent, unchallenged power. Below, the quotation from Alexander Pope reads, in part, ‘More he had said – but yawn’d – all nature nods: / What mortal can resist the yawn of gods?’ The caption is ‘Lo! What are all your schemes come to?’: Bickham revels in his satisfaction that his god-like target has been felled.

Johnson, on the other hand, is still with us, at least for the time being. Our satirists must wonder when they’ll be able to turn on some other victim. And perhaps, considering that the aim of the satirist is to mock through exaggeration, they sometimes despair of their job. Johnson is so grotesque and extreme a figure, in his personal appearance, amoral behaviour and inept government, that they must wake up in the morning wondering how they can possibly paint him in yet more lurid colours.

Leave a Reply