The first society in Wales devoted to the study of archaeology, the Cambrian Archaeological Association, was founded in 1847, largely through the efforts of two Welsh clergymen, Rev. Harry Longueville Jones (1806-1870) and Rev. John Williams, ‘Ab Ithel’ (1811-1862).

Longueville Jones, London-born and not a Welsh speaker, had led a varied life: he was educated at Cambridge, became lecturer and dean of Magdalene College, took holy orders, though without proceeding to a living, founded a college in Manchester, moved to Paris in 1834 and was living at Llandegfan, Anglesey in 1846.

Williams, a Welsh speaker born in Denbighshire, attended Ruthin Grammar School and Jesus College, Oxford, before taking orders and accepting a series of livings; by 1843 he was perpetual curate at Nercwys, near Mold.

The circumstances in which the two men came together are significant, especially in the light of the High Church origins of the nineteenth century archaeological revival (1). In 1835 the Ecclesiastical Commission of the Church of England made a proposal to unite the dioceses of Llandaff and Bristol and to merge Bangor and St Asaph (2). The idea met with fierce opposition from many Anglicans, especially in North Wales, including both Ab Ithel and Longueville Jones, who met in Manchester during the campaign to defeat the Bangor-St Asaph proposal. As part of his contribution to the campaign Ab Ithel published in 1844 his Ecclesiastical antiquities of the Cymry, in which he sought, as he makes clear in his preface, to justify the institutions of the Welsh Church by tracing their history back to the remotest times. Meanwhile, Longueville Jones was attacking the inactivity of the Bangor diocesan authorities, who were allowing several churches in Anglesey to fall into ruin (3).

A shared interest in Church politics and history led naturally to a wider concern for Welsh archaeology and early history. Aware that a widespread interest in these subjects existed in Wales, Longueville Jones and Ab Ithel published in January 1846 the first issue of a new Engish-language periodical entitled Archaeologia Cambrensis. In the preface the editors hoped that ‘by describing and illustrating the antiquities of our dear native land, we shall meet with the lasting support and sympathy of all, who love those venerable and delightful associations connected with the very name of Wales’ (4). There followed a miscellaneous collection of articles on various topics, beginning with a manifesto by Longueville Jones called ‘On the study and preservation of national antiquities’. In it he proposed the establishment of local archaeological societies to examine and guard local antiquities: ‘…We have societies for the whole empire, but we want more numerous local associations. Wales in particular, though rich in antiquities, is peculiarly defective in her organisation for their study and their preservation; and if we except the Society for the Publication of Welsh MSS., there is hardly any antiquarian body to be found in the Principality possessing features of vitality and activity’ (5). This suggestion was taken up in the next issue by ‘A Welsh Antiquary’, writing from London, who proposed that ‘an Antiquarian Association be formed, to be called ‘The Cambrian Archaeological Association for the study and preservation of the National Antiquities of Wales” ‘(6). The editors replied by soliciting the approval of their readers for the plan. By the end of 1846 ninety of ‘the most active of our Cambrian Antiquaries’ had written giving it their support, and the society was officially established on 1 January 1847.

The Archaeological Institute was taken as a model for the organisation of the new association. The laws and regulations of the AI were provisionally adopted, as was its practice of holding annual meetings in different towns. This was more a matter of necessity than of choice: ‘As Wales does not possess any metropolitan city where the Association could have a permanent locality, it must of necessity become an ambulatory body, and must hold meetings at fixed periods in various places’ (7). The first meeting, held at Aberystwyth in September 1847, lasted three days and included business meetings, the reading of papers and visits to interesting sites of archaeological and historical importance, a report of the proceedings following in Arch. Camb.

This pattern was adhered to with few variations throughout the nineteenth century and survives to the present. A different town was visited each summer, with a tendency to alternate between north and south Wales, and with occasional excursions to towns in the Marches and other Celtic countries. The summer meeting was the only occasion during the year when all the CAA’s members could assemble together. The affairs of the Association during the rest of the year were in the hands of a Committee and the Officers, the most important of whom were the editor of Arch. Camb. and the Secretary. It was these men who effectively guided the society in the directions it was to take. Apart from the example of the Archaeological Institute two other factors were at work in the movement to form the CAA: a profound sense of Welsh patriotism, and a recognition that progress in the study and preservation of Welsh antiquities could no longer depend on the independent efforts of a few isolated individuals, but must proceed in a more systematic and scientific manner, with scholars working co-operatively towards the fulfilment of previously agreed aims.

Political nationalism still lay in the future, but by the mid-nineteenth century a strong sense of a Welsh national identity, based on a revived interest in the Welsh language and the rapid spread of nonconformity after 1800, had entered the consciousness of both working class and middle-class Welshmen. The cultural expression of this feeling was evidenced in the growth of Cambrian, Cymmrodorion and Cymreigyddion societies in all parts of Wales, and in the campaign against any alterations in the structure of the Welsh dioceses in the 1830s, which was in essence patriotic in inspiration. Perhaps the most articulate expression of it came in 1847, when the publication of the report of the Education Commissioners, which had criticised in hostile terms the moral, social, religious and educational condition of Wales, provoked immediate outrage among Welsh people at the contempt shown to Welsh life and institutions.

It was not only nonconformists who sprang to the defence of Wales and condemned this ‘Treachery of the Blue Books’: many Anglican clergymen also felt affronted by the insulting tone of the Commissioners and were eager to assert the independence and cultural separateness of their nation. It was in this climate that Longueville Jones and Ab Ithel saw, in the formation of the CAA, an opportunity to establish Wales in the field of antiquarian studies as an equal partner with England: it possessed antiquities and an historical tradition of profound interest; it should therefore be provided with a society, a journal and a scholarly tradition to match those of England. No longer would supercilious English writers be able to describe Welsh monuments as wholly unstudied, neglected and uncared for.

It was Ab Ithel who felt most keenly the low standing of Welsh learning within the British antiquarian tradition. The intention of his Ecclesiastical antiquities of the Cymry was partly to reveal to his English readers what a mighty contribution the Welsh had made to the development of Christianity in Britain. The evidence he used to support this thesis, derived as it was from the ‘Iolo Manuscripts’, to which he had access, was at best dubious and speculative, at worst spurious, but since so little of it had been published, and since so few of his readers were equipped with the necessary critical skills, no objective assessment of it was possible. Ab Ithel’s assertions about the autochthonous Welsh, their Bardic traditions handed down from the Druids in prehistoric times to the present, and the Druidic uses of megaliths, stone circles and chambered tombs therefore went unchallenged, even when they began to appear in the pages of Arch. Camb. (8).

Longueville Jones’s approach to archaeology was much more cautious and less dogmatic: ‘It is not… by any means easy to determine, first, at what period Christianity was actually introduced into Wales and Anglesey; and secondly, to pronounce what remains usually classed as Cymric or Celtic … were erected before, or what after, the existence of the Christian religion in this district …’(9). Scepticism of this kind about the classification of ancient monuments went hand in hand with an insistence on the application everywhere of a systematic method in the recording, preservation and interpretation of antiquities. It is clear from his manifesto article in volume 1 of Arch. Camb. that he was concerned only secondarily with reasserting the honour of specifically Welsh antiquarian scholarship: his main purpose was to promote a general change of taste, especially towards the rehabilitation of medieval architecture. But it was not simply a question of a personal commitment to preserve the past; the antiquary ‘must not only be fond of studying and preserving objects of antiquity, but he must also know how rightly to do so’ (10). ‘He who allows his imagination to run too far ahead of his facts, and plunges into generalizations without documents or monuments to support them, stands not only in his own light, but also in that of others, and hinders, instead of forwarding the general work’ (11). Longueville Jones goes on to urge the importance of respecting the monuments of the past. ‘The need is for a national association without which there can be no unity of action, no communication of discoveries and ideas, no “division of labour”, no “mutual encouragement”; all is left to the desultory exertions of individuals, and not a tenth part of the good is done, which might be accomplished by the combined exertions of the whole body of Welsh antiquaries’ (12). Combined action required a plan of action: ‘Much more progress can be made in archaeology … if a well-digested and comprehensive plan be kept in view and acted upon.’ (13). Accordingly, he suggests as a preliminary step that complete lists should be prepared for each county in Wales of all monastic buildings, churches, castles, old houses and medieval documents.

Longueville Jones’s conception of the CAA, then, was not simply that of a clearing-house for the views of Welsh antiquaries, each pursuing independently his own particular branch of enquiry, but as a coherent organisation coordinating an agreed programme of research by members working in close co-operation with one another. Its primary work was to be descriptive, and therefore scientific. Its basis, though cultural and even moral, was not patriotic, or at least chauvinistic: the words Wales or Welsh hardly occur in the article. There was no suggestion that its foundation was connected with a wider and specifically Welsh cultural movement. The contrast with the views of the fiercely defensive Ab Ithel could not be greater. Despite warnings to avoid the bitter rifts suffered by other archaeological societies, notably the British Archaeological Association (14), a clash between the two men was inevitable. Sir Ben Bowen Thomas has described in detail (15) the chain of events which led in 1853 to the resignation of Ab Ithel as editor of Arch. Camb. and member of the CAA, and to his launching of a competitor society, the Cambrian Institute, and a rival journal, the Cambrian Journal. The Cambrian Institute seems in fact to have had little existence outside its creator’s mind, and the Cambrian Journal survived until only 1864, two years after Ab Ithel’s death. Resignations from the CAA in sympathy with Ab Ithel were few and there were no further serious divisions. The Association had turned its back decisively on the wider romantic approaches to history and prehistory.

It is worth considering at this point the membership of the CAA at its establishment and as it changed during the period in question. The first list of members was published in the January 1847 issue of Arch. Camb. The total number of members was 128. As many as 50 of these were clergymen, including all four Welsh bishops. This was, of course, the social circle in which Longueville Jones and Ab Ithel moved, but throughout the nineteenth century Anglican clergy played a crucial role in the Association’s affairs, as they did in other archaeological societies (16). In 1867 they numbered 64 out of a total of 283, and in 1873 77 out of 309. Many of the leading members of the CAA in the period were clergymen: W. Basil Jones, Bishop of St David’s, D.R. Thomas and D. Silvan Evans. Anglican churchmen enjoyed both the education and the leisure to take an active interest in their native antiquities and history.

On the other hand, nonconformist ministers are conspicuous by their absence. In view of the sectarian rivalries in nineteenth century Wales this comes as no surprise. Edward Hamer wrote in 1867 ‘… the mass of Dissenters look upon the Society either with disapprobation, or a species of jealous suspicion. Why they should be so, is not very clear, unless that its leaders are churchmen, and that the members take too deep an interest in church architecture, ecclesiastical relics, etc.’ (17). He was told that they disapproved of any interest in antiquities because the latter were ‘vanities entirely which ought to be left in the hands of churchmen or Roman Catholics’. The feelings of suspicion, it should be said, were mutual: R. Goring Thomas asked Longueville Jones in 1848 whether any CAA funds were used to build or restore churches: ‘From the fact of your Local Secretary for Caermarthenshire being a Dissenter I apprehend not’ (18). Not only were the supporters of the CAA members of the established church, some of them, notably Ab Ithel, W.W.E. Wynne and, in his early days, W. Basil Jones, sympathised with the Oxford Movement, which had a certain following in parts of Wales in the two decades after 1841 and which aroused widespread suspicion of leanings towards Papism.

Hamer draws attention to another important factor discouraging nonconformists from participating in the CAA, the linguistic divide between the mainly Welsh-speaking dissenters and the English-speaking Association: ‘The transactions of the Society are carried on in the English language – a language which a large proportion of the people do not yet understand, and upon which many … look with what they deem a patriotic indifference, which leads many of them to take no interest in the Society’ (19). Throughout the nineteenth century not one article was published in Arch. Camb. in the Welsh language. This was partly in deference to the many members who were either Englishmen or monoglot English-speaking Welshmen, and partly because the leading members of the Association wished the CAA to take its rightful place in the forefront of British archaeology, and English was necessarily the lingua franca of archaeological discussion.

Finally, by the mid-nineteenth century there was also a strong political as well as a linguistic divide between Anglican and Dissenter. Many Anglican clergy belonged to the same class, and held the same conservative political views as the anglicised gentry who constituted the other main group of CAA members. Seven of the 128 members in 1847 were titled, and many more belonged to the gentry. These were mostly members of old Welsh families, now anglicised in speech and way of life, and socially remote from the common people in the areas where their country houses were situated. They constituted the ruling class in all parts of rural Wales until the 1880s: they acted as both magistrates and local administrators in their capacities as J.P.s, and they exercised great economic and political influence on their tenants (20). Apart from the fact that they had often received a good education in England and enjoyed abundant leisure, their interest in history and archaeology can be attributed to two particular factors. Firstly, although most of them were ignorant of the Welsh language and could not therefore participate in the literary culture of their native land, they were proud of their Welshness and of their genealogies, which they could trace back to medieval times and earlier; a knowledge of and interest in their forebears provided for them part of a justification of the privileged positions they enjoyed within society. Secondly, many of them, by virtue of inheritance, bequest or marriage, had in their possession physical manifestations of the distant past – either ancient monuments which happened to lie on their estates, or manuscripts in their libraries which had been handed down through the generations. So, for example, W.O. Stanley, MP, examined and excavated a number of sites on his estate near Holyhead in the 1860s and 1870s, and W.W.E. Wynne studied and catalogued the Hengwrt manuscripts bequeathed to him in 1859.

Because most of them were Anglican in religion they also had an interest in studying and preserving the ancient churches of Wales, which by the nineteenth century were suffering badly from neglect and decay. Those members of the CAA who owned ancient monuments were continually reminded of the moral obligation they were under to preserve them: ‘It cannot be too strongly impressed upon the nobility and gentry of the land that they are, by virtue of their station, the natural conservators of the historical monuments of their country, and that they are bound to protect them, even at the expense of their money and their leisure’ (21). The CAA relied on the wealth of the ‘nobility and gentry’ not only to preserve Welsh monuments, but also to support its own activities. Membership was at first free and Arch. Camb. was apparently published at the expense of Longueville Jones (22); from 1850 only subscribing members were admitted, at an annual fee of £1.00. However, the editors frequently had to resort to appeals for extra funds to enable them to incorporate illustrations in Arch. Camb. or to issue special publications.

Besides the clergy and the gentry, a third group played an increasingly important in the CAA’s affairs, the professional and commercial middle class. Many were English commercial or industrial entrepreneurs, attracted by the opportunities offered by the massive industrial expansion of South Wales in the second half of the nineteenth century. The 1847 list includes no less than four professional architects; later industrialists like G.G. Francis, J.E. Lee, engineers (G.T. Clark, J.R. Allen), lawyers (M.C. Jones, T.O. Morgan), chemists (A.N. Palmer, Thomas Stephens) and many others made notable contributions to the Association’s activities. Each of these could use his own professional expertise in the service of antiquarian scholarship – Clark, for example, in his studies of Welsh castles. But, with the exception of Edward Freeman, it was only towards the end of the and nineteenth century that university-based professional historians and archaeologists, such as John Rhys, A.H. Sayce and Francis Haverfield, brought to the CAA the academic rigour often lacking in the study of Welsh history.

The CAA was solidly upper- and middle-class in composition: it would be difficult to point to a single working-class member in the period under consideration. Another large class of people largely absent is that of women. In 1847 a new category of ‘Honorary members’ was introduced to cater for ‘those ladies who may honour the Association with their names’ (23). There were initially five such members, including Lady Llanover, Angharad Llwyd and Jane Williams of Talgarth, but after the introduction of subscriptions in 1850 nothing further is heard of them or of ‘Honorary members’. In 1850 there were only five female members out of 119, in 1873 only 17 out of 274. This is a far smaller proportion of women than one might expect to find in a nineteenth century local archaeological society.

The only social occasion in the CAA’s calendar was the annual summer meeting. At these meetings each gentleman member could buy a ticket admitting him and two ladies to all the proceedings (24). There was much to enjoy besides the inspection of antiquities and the reading of learned papers: daily visits, by carriage or on foot, to interesting sites, exhibitions of antiquities and curiosities, and, in the evenings, dinners and entertainments. At Caernarfon in 1848, for example, the business was followed by tea and coffee, and then the Harmonical Society of Caernarvon’ sang some select pieces, and a quadrille band, hired for the occasion, performed some favourite Welsh airs (25). How heavily the CAA relied on the services of women to ensure the success of summer meetings from a social point of view can be gathered from a letter Thomas Wakeman sent to Longueville Jones in 1848: ‘You may depend upon it, the next meeting at Cardiff will be well attended. I have set the Ladies to work heart and soul to promote it and we have some of the right sort here to carry it out’ (26).

A numerical analysis of the membership of the CAA during the period under review reveals three main phases. The first few years, from 1847 to 1854, saw a moderate rise in members from 128 to 154, as word of the new society spread through Wales and beyond its border. Then there was a rapid increase of 142 members between 1854 and 1857, after the departure of Ab Ithel, followed by a long period, until about 1890, when the membership remained remarkably static at between 274 and 324. During this period occasional complaints in Arch. Camb. drew attention to the failure to attract new members: ‘An old member’ pointed out in 1866 that the average number of 300 members compared unfavourably with some of the English antiquarian societies, notably those of Sussex (605 members) and Kent (885) (27). Finally, from 1889 until the outbreak of the First World War, numbers increased rapidly and almost continuously, from 284 to a peak of 510. This dramatic rise reflected accurately the enormous quickening of interest in archaeology and local history around the turn of the century, not only in Wales but throughout Britain, and it is no accident that it was at this time that most of the local archaeological societies in Wales were founded.

It is also instructive to consider the geographical distribution of CAA members during the same period. 58 of the 128 members during the first year, 1847, came from north Wales, where Longueville Jones and Ab Ithel were both active, but already by 1850 south Wales had overtaken the north, with twenty-five members from Glamorgan alone, largely the result of an influx of historically-minded members of the local societies already in existence – the Royal Institution of South Wales, the Neath Philosophical Society and the Caerleon Antiquarian Society. The local membership of the CAA was often boosted by the holding of the annual summer meeting in the vicinity: after the first meeting at Aberystwyth the Cardiganshire contingent increased from two to twenty. Similarly, the number of Brecknockshire members leapt from three to fifteen after the Brecon meeting of 1872, and the number of Pembrokeshire members from eight to sixteen following the Tenby meeting in 1851. This stimulating effect of CAA visits. was deliberately encouraged by the officers; one of them noted, ‘The meeting of 1907 was attended by an unusually large number of members, and one purpose of these annual gatherings, viz., to stir up local interest, was certainly attained, as was evident from the considerable influx of non-members, many of whom gave notice of joining after the appointed date for such notice…’ (28).

The activities of the CAA may be divided broadly into three areas: the publication of historical and archaeological research, the promotion of archaeological excavation and fieldwork, and the preservation of ancient sites and objects. Each will now be considered in turn.

Publications

The quarterly issues of Anch. Camb. provided the active members of the CAA with abundant space to publish their excavation and fieldwork reports, theoretical essays, historical dissertations, notes on new discoveries and polemical correspondence. The public communication of new discoveries and theories was seen by its founders as one of the chief purposes of the CAA, and its journal soon established itself as the natural repository of historical and archaeological thought and information within Wales. Indeed, in 1857 the Editor could claim prior right to publish any material on Welsh antiquity: ‘If we mistake not, the Cambrian Archaeological Association has done enough for Wales to entitle it to the right of absolute pre-emption in everything that refers to Welsh archaeology’ (29).

The pattern of each volume altered little over the years: substantial articles were followed by briefer notes on archaeological finds or historical minutiae, correspondence and book reviews; a detailed report was always given of the annual summer meeting, summarising the papers delivered and the visits made. Engraved illustrations, which accompanied many of the articles from the first volume onwards, were superseded gradually from 1858 by photographs. Throughout the period the format of Arch. Camb. was quarto: unlike Archaeologia, which was folio, it was therefore not suitable for the inclusion of large, detailed archaeological plans. From time to time supplementary volumes were issued, most of them transcriptions of hitherto unpublished manuscripts of historical importance.

Turning to the subjects dealt with in Arch. Camb. articles, the most noticeable trend is a decline, starting in the late 1880s, in the number of historical, document-based articles, as opposed to the mainly archaeological articles. This decline reflects not only the increase in interest in archaeology in the last years of the nineteenth century, already referred to, but also the predilections of the editor and the other CAA officers. From the early 1890s the pages of Arch. Camb. are full of pleas for more archaeological contributions, largely from the pen of the archaeologically minded editor, J. Romilly Allen (30). Similarly, the prevalence during the early years of articles on medieval buildings and antiquities is attributable to a large degree to the example and influence of Longueville Jones, who contributed a long series of articles on medieval Anglesey and Arfon from 1846 to 1863. However, the editors could only encourage and urge: they could not commission or direct contributions from members. The popularity or neglect of particular archaeological subjects was therefore mainly a function of the interests of a small minority of active members of the CAA and other, outside contributors. For example, the Association was fortunate to be able to rely on the services of J.O. Westwood and later Sir John Rhys for the continuous series of articles and notes on the ogham inscriptions of Wales, which make up the bulk of the ‘post-Roman’ category. Conversely, the paucity of contributions on the Roman period simply reflects the lack of interests shown by antiquarians in the subject, in spite of a spirited and rare attempt by a group of members to launch a systematic survey of Roman Wales, ‘Cambria Romana’, in 1847 (see below). Despite complaints from J.R. Allen (31) the subject lay dormant until Francis Haverfield rescued it in 1903 with his article on Roman forts in South Wales (32). By this time Arch. Camb. had lost what monopoly it could previously claim to the publication of new discoveries in Wales; the annual report for 1903 regretted that ‘although discoveries of Roman remains of great importance have been made at Caersws, Cardiff, Gellygaer, and Caerwent, no account of them has been sent for publication in the Journal’ (33).

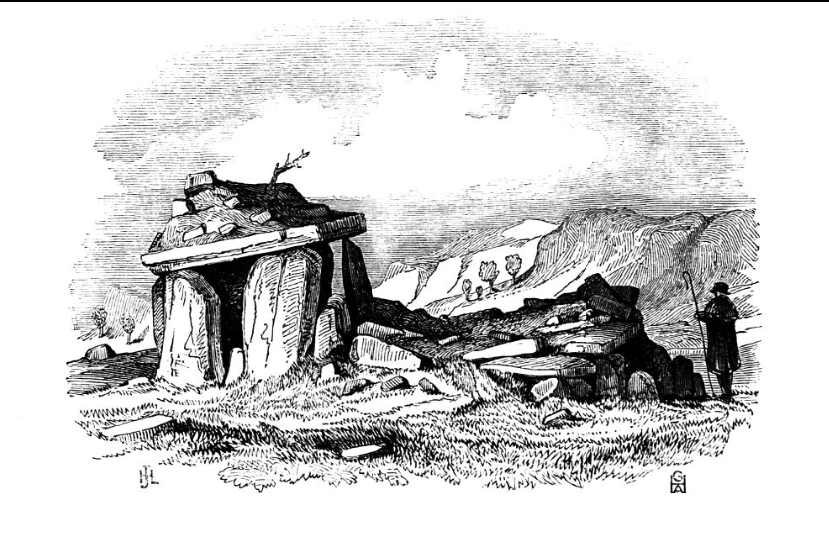

The study of prehistoric Wales fared better. The earlier volumes featured many articles on cromlechs, but discussion was clouded by the ‘bardic’ controversy of Ab Ithel. Later came a steady stream of articles from writers on particular types of monument or particular regions, for example, W.W. Foulkes on the Clwydian hill-forts and Denbighshire tumuli, E.L. Barnwell on cromlechs and W.W. Williams and H. Prichard on the prehistoric monuments of Anglesey, some based on excavations, others on observation and comparison. Few sites were described with accurate and fully measured plans, and illustrations, though plentiful, tended to conform to the picturesque style well after 1846 (34). More serious, although the pioneering work of Daniel Wilson, Tomsen, Worsaae and Boucher de Perthes was reported promptly and in detail in Arch. Camb., no one in Wales succeeded in developing a theoretical framework within which to interpret Welsh prehistoric antiquities.

The ‘Miscellaneous Notes’ column in Arch. Camb. was intended as a repository for brief information on recent discoveries and finds, but its purpose was not well fulfilled. Throughout the nineteenth century the Local Secretaries were frequently berated for failing in their duty to notify the editors of recent developments in their counties.

Excavation and fieldwork

The importance of excavation in archaeology became apparent to the early Cambrians in the first volume of Arch. Camb., which contained an account of excavations within the site of the Roman fort of Segontium at Caernarfon. It appears that the Editors were responsible for obtaining a grant of £5 towards the cost of the project from the British Archaeological Institute, and the CAA Treasurer, James Dearden, himself donated £21. Future excavations were often financed by personal contributions. Alternatively, a subscription was raised, as for Foulkes’s excavations in the Clwydian hill-forts (35) and those of David Davies at the Roman fort at Caersws in 1854-55 (36). The subscription method developed naturally into a system of local committees to manage excavations. An early example was the committee set up in 1853 to organise E.A. Freeman’s excavations at Leominster Priory (37), but the use of the committee system did not become widespread until the 1880-1890s, with excavations at Strata Florida Abbey, Talley and Strata Marcella, continuing after the War with Segontium from 1919. These committees were responsible for overseeing the work of the excavator, raising money to finance it, and caring for the excavated site and the finds unearthed. With the additional income derived from its increased membership the CAA now felt able to make grants towards the costs of excavations more frequently: from 1886 to 1890 several grants were made to Stephen Williams‘s excavations at Strata Florida; among later excavations aided were those at St David’s Head, Caerwent, Gelligaer and Cwmbrwyn (38).

However, it became evident to some archaeologists (significantly, from outside Wales) that the ad hoc nature of local committees and the uncertainty of funding by voluntary bodies were not conducive to effective excavation, and more permanent solutions to the problem were sought. In 1907 the Liverpool Committee for Excavation and Research in Wales and the Marches, based on the University of Liverpool’s School of Archaeology, was formed. Its purpose was to plan, fund and carry out a systematic programme of excavations in Wales ‘on proper scientific lines’. Its first organising secretary was A.O. Vaughan (‘Owen Rhoscomyl’). Under its auspices excavations were carried out at Caerleon in 1908-9 and at Caersws in 1909 (39), but its effect was not as great as its founders must have hoped. Only one annual report was published and the Committee became inactive shortly afterwards. A second initiative came in 1911, when papers were read to the Cymmrodorion Section at the Carmarthen National Eisteddfod by J.E. Lloyd and R.C. Bosanquet proposing a greater degree of organisation in Welsh archaeological and historical research (40). As a result, a resolution was passed that a fund should be established ‘to be administered by a committee composed of representatives of the existing historical and antiquarian societies of Wales, for the purpose of doing excavatory and other necessary archaeological work on a definite scientific system’ (41). The Council of the Society endorsed the proposal but it was never put into practice, probably because of lack of funds (42).

In 1918 the organisation and funding of Welsh excavations were still felt to be unsatisfactory. In that year John Ward, perhaps the most capable of the early excavators, wrote to G.G.T. Treherne, ‘How constantly it has been difficult or impossible to carry out an exploration according to a scheme on a/c of the uncertainty of funds! Some work has cost double on account of stoppages & so on. Nearly all my archaeological work has been rendered trying, on account of committee wobblings and cheeseparing, & humbugging bounders set over me or made my colleagues’ (43). When archaeology recovered after the First World War, new methods of funding began to emerge: the excavation in 1926 of the amphitheatre at Caerleon was financed by the Daily Mail in exchange for exclusive news of the results: archaeology was taking hold of the imagination of a much wider public than ever before. The post-war period also saw the National Museum under the directorship of Mortimer Wheeler take a leading role in excavation, with campaigns at Brecon Gaer (1924-5), and Caerleon (from 1926) (44).

Techniques employed in excavations recorded in Arch. Camb. improved little until towards the end of the nineteenth century. At Tomen y Mur Roman fort in 1846 ‘the party, being provided with a light pickaxe and crowbar, such as are used by foumart hunters, were enabled to dig into and lay open portions of another wall or house’ (45). Two years later the excavation of Roman coffins near Caerleon succeeded in breaking both the coffins and the glass found nearby (46). In 1860 John Fenton was recommending to readers the same unscientific methods of opening cairns as had been employed 50 years before (47). In 1873 a tomb was opened near Dolgellau by means of a crowbar and a team of horses, after blasting had been considered but discounted. Some Cambrians, however, were aware of the problems of excavation and were more careful in their practice. Longueville Jones had a particularly advanced conception of excavation. He protested vigorously against the ‘rash and unauthorised opening of tumuli’ (48); ‘…until such valuable monuments of our early fathers can be opened in the presence of those who fully appreciate their value; until there can be some person on the spot able and ready to note down, to criticize, and to delineate their contents; and still more, until local or national museums can be formed, wherein the articles, which these tumuli contain, can be deposited, I would most strongly advise all owners of land, upon which they occur, to be very cautious how they allow them to be disturbed…’ (49). He saw clearly that to excavate is to destroy, and found it necessary to repeat the point many times in Arch. Camb. (50).

One archaeologist whose excavations do seem to have been carried out with a modicum of care was W. Wynne Foulkes, who worked on hill-forts in the Clwydian range and Denbighshire tumuli in the early 1850s. He had an elementary understanding of stratigraphy. An urn he discovered below the original surface of a rampart he regarded as ‘a fact somewhat material in determining the age of the rampart and the white pottery’ (51), and he included a sketch of the section through a rampart of Moel Gaer in his report (52). He was careful to have the bones discovered in an excavation of tumuli in Denbighshire sent for analysis to the College of Surgeons (53). He accepted the three-age system of Thomsen and Worsaae and interpreted his discoveries with the aid of it. However, even Foulkes, in some of his tumulus excavations, resorted to the same inadequate methods as Richard Fenton: sinking a circular hole in the centre of the mound (54).

Nor was he as scrupulous as he might have been about measuring and recording what he found, as he himself once admitted (55). It was not until towards the end of the century that excavation standards began to improve as more competent, professional archaeologists took the field. The outstanding excavator at this time was John Ward. Appointed curator of Cardiff Museum in 1893, Ward was responsible for the carefully executed and meticulously recorded excavations at Tinkinswood burial chamber, Gelligaer Roman fort, Cwmbrwyn Roman settlement and elsewhere. As Glyn Daniel remarked, ‘…reports of [his] fine excavations still make stimulating and thoughtful and clear reading’ (56).

The history of archaeological fieldwork in Wales in the nineteenth century is one of unfulfilled ambition. In his manifesto for Arch. Camb. Longueville Jones proposed the compilation of a series of surveys of existing archaeological remains and historical manuscripts, including ‘complete and accurate surveys, measurements, delineations, &c.’ (57): a Monasticon, an Ecclesiasticon, a Castellarium, a Mansionarium, a Villare and Pariochiale, and a Chartularium. These surveys were to be built up from the voluntary contributions of individuals, working within the framework of sets of instructions or questionnaires, some of which were later printed in Arch. Camb. This cooperative method was often advocated in succeeding years (58), but, with one exception, was never translated into practice, much to the regret of Longueville Jones (59).

The exception was the project known as Cambria Romana. In 1847 a ‘club’ or informal subsection of the CAA was formed, with the aim of compiling a complete ‘Cambria Romana’ or survey of Roman antiquities in Wales and the border counties, on the same lines as Robert Stuart’s recent Caledonia Romana (60). Members were enlisted to cover most of the counties (61). Cardiganshire was in the process of being surveyed before the end of the year, and Merioneth and Montgomeryshire were almost complete by 1851 (62). However, in 1853 Longueville Jones acknowledged that the survey was proceeding ‘ in a far more desultory manner than could be desired’ (63). The work gradually lapsed, and in 1869 Longueville Jones had to confess that ‘the survey of Roman remains in Wales, carried on by two or three zealous members, seems at present suspended, and in danger of being forgotten’ (64). No more was heard of Cambria Romana and its work was indeed forgotten.

Fieldwork was, therefore, carried out, for the most part, in an uncoordinated way by individual scholars as inclination or chance dictated (65). One inch to one mile Ordnance Survey maps were available for the whole of Wales and were often recommended for use in plotting the courses of Roman roads. During the final decades of the century maps on larger scales were being prepared and provided the framework for more detailed archaeological surveys. Once again J.R. Allen was in the forefront of the movement to survey systematically the antiquities of Wales. Writing in 1888 about Roman finds in Wales, he regretted ‘an entire want of system in the methods of investigation employed’ in plotting the course of Roman roads. He proposed a catalogue of Roman finds, roads and stations, each to be marked on the Ordnance Survey map by a team of CAA members, each of whom would be responsible for a particular district. Furthermore, survey parties could be organised at the annual summer meetings ‘with the object of tracing some portion of a Roman road carefully through its length’. ‘The fact is that the rushing about from church to church and from cromlech to cromlech, which takes place at the annual excursions, goes a very small way towards solving those archaeological and historical problems for the investigation of which the Association was formed. We have now, as a body, been at work for 40 years, and during that time, with perhaps the exception of the early inscribed stones, no single subject has been systematically treated as a whole, nor has any one locality been exhaustively surveyed, so as to leave nothing to be gleaned hereafter.’ (66).

Five years later Allen returned to the same subject, proposing the preparation of classified lists of all ancient remains in Wales, and their plotting on 6 inch Ordnance Survey maps for each county. Finally, at a CAA Committee meeting at Shrewsbury in April 1893 a committee was appointed, with Allen as Secretary, to devise a scheme for an Ethnographic Survey of Wales, in collaboration with the Ethnographic Survey Committee of the British Association (67). In 1895 it reported that the CAA would be responsible for the archaeological part of the Ethnographic Survey, that the plan had been submitted to and accepted by the BA, and that Glamorgan had been selected as the first county was to be surveyed (68). However, work never seems to have begun in Glamorgan, and Edward Lawes and Henry Owen were asked to commence the survey in Pembrokeshire, thought to be suitable because of its richness in both antiquities and antiquaries (69). They set up a local committee of supporters and began work in 1896 (70). The first instalment, recording sites and finds in the Tenby area, was ready quickly, and it was suggested that the completed sheets and schedules should be printed and sold to the public (71). Excavations were conducted by James Phillips in an attempt to elucidate some of the problems raised by the survey A Pembrokeshire bibliography was published by Henry Owen, and an antiquities column was started in the Pembroke County Guardian, through the influence of the editor, H.W. Williams of Solva, who was a member of the Committee (72). The work progressed slowly, partly on account of the voluntary nature of the contributions: in 1901 Laws complained, ‘I may say that the work would have been completed last year, had it not been for the sadly dilatory ways of some of our workers. Gentlemen undertake a district, receive the quarter-sheets, and then put them away for years’ (73). Laws had to carry out much of the surveying himself. By 1907 he confessed himself too old to continue, and handed the project over to Henry Owen, who would continue the work at his own cost (74). At last the work was completed and published in 1908, after twelve years.

An extension of the survey to other counties was not even considered by the CAA: the work was clearly far beyond the capabilities of a voluntary organisation with few resources and an unreliable supply of researchers. Furthermore, October 1908 saw the establishment of a statutory, publicly-financed body with the task of executing archaeological survey work for the whole of Wales, the Royal Commission on Ancient Monuments (Wales). Its remit was to ‘make an inventory of the archaeological and historical monuments and constructions connected with or illustrative of the contemporary culture and civilisation and condition of life of the people of Wales from the earliest times, and to specify those which seem most worthy of preservation’.

Already by the First World War five inventories were published, for Montgomeryshire (1911), Flintshire (1912), Radnorshire (1913), Denbighshire (1914) and Carmarthenshire (1917). The preface of the Montgomeryshire inventory identifies the reasons why such achievements were unattainable by the voluntary societies, ‘where there is no strong directing organisation, and where each contributing member takes up his plot and ploughs his lonely furrow regardless of the researches of his fellow members’. Despite the uneven quality of the early inventories, it was clear that the large-scale surveying of monuments had been taken permanently out of the hands of enthusiastic amateurs, and that the state had at last assumed an important role in British archaeology. It should be said, however, that the Commission had to rely, in the absence of a trained body of professional archaeological surveyors, on the cooperation of many local antiquarians, some of whom were appointed as ‘local correspondents’ for particular districts (75), and so, in an informal way, members of local societies continued to contribute to archaeological surveys.

Preservation

The founders of the CAA regarded the preservation of ancient monuments, sites and objects as one of the chief concerns of the new organisation. A notice to correspondents stated, ‘Early information of any projected alteration, mutilation, or destruction of monuments of any kind, will be gladly received; and the Editors will do their best, by informing the antiquarian world and by communicating with the proper authorities, to prevent or remedy any damage threatened or done’ (76). In his initial manifesto article in Arch. Camb. (77), Longueville Jones wrote a passionate and lengthy plea for the saving of ancient monuments and a halt to the process of destruction. He identified four classes of destroyers: ‘needy or tasteless owners of property’, government and municipal corporations, public companies, and restorers.

Landowners frequently lacked the money to maintain the monuments they owned or the knowledge and taste to appreciate their value. It is worth bearing in mind that virtually all of the Welsh castles were in private hands at this time; the expenses incurred in their preservation could be considerable, even for substantial property owners.

Local authorities also often lacked the ability to recognise and preserve antiquities in their care. In 1859 the Lampeter magistrates were responsible for tearing up and destroying a length of Roman road and converting it into a common road (78). In the 1860s the authorities of Tenby were with difficulty prevented from demolishing the medieval town walls. As late as the first decade of the twentieth century, it was alleged that councils were busy destroying cromlechs and tumuli for road-mending in Anglesey and Cardiganshire (79).

A more common cause of destruction was the effect on the Welsh landscape of industrialisation, especially in Glamorgan. Longueville Jones warned in 1869 that work on prehistoric antiquities in the county should not be delayed ‘if only on account of the rapid change induced upon the district by the effects of modern industry and activity’ (80). Especially significant was the effect of the construction of canals and railways. By 1850 14 privately-built railways had been completed in Wales; scores more followed in the succeeding decades. In the process it was inevitable that antiquities would be uncovered and destroyed (81). Not every company owner, contractor or engineer was as scrupulous in his respect for what was unearthed as I.K. Brunel, who, in the enlarging of a canal near Llanthony Abbey in 1852, had ‘requested the contractor to preserve with care any relics his men might find’ (82). J.O. Westwood gives a graphic account of the difficulties he faced in tracing early Christian stones as a result of the reckless transformation of parts of Wales for the sake of commercial gain: …railway cuttings, new buildings, change of tenants and farm servants, and, worst of all, heedlessness of the value of such precious memorials, rendered my search a laborious one. The locality is now transformed into the Port-Talbot Station of the South Wales Railway…’ (83). In other parts of Wales agricultural improvements, sponsored by the many county agricultural societies established at the end of the eighteenth century, and the contemporary enclosure movement, also had an effect on the landscape and the preservation of vulnerable ancient sites (84).

But most of Longueville-Jones’s vitriol, in his catalogue of destructive agents, was reserved for the restorers of medieval buildings, chiefly churches: ‘the beautifiers, the repairers, the restorers, the new-builders, and all that category of well meaning, yet oft-times misled, individuals’ (85). By the end of the eighteenth century very many Welsh churches had fallen into disrepair through neglect and indifference, and the diocesan authorities, spurred on by a revived spirit of confidence, engaged a wide variety of architects, some nationally known, like G.G. Scott and G.E. Street, others local, like R.K. Penson and J.L. Pearson, to repair, restore or rebuild them. All of these architects worked in the new style of the Gothic revival, aiming to recover and revive the style and spirit of medieval church architecture; many were keen antiquarians and became members of the CAA (Penson, H. Kennedy and S.W. Williams). But some of the results of their work did not meet with the approval of their fellow antiquaries. Often a church was entirely demolished and replaced by a new one (86), but no less serious was injudicious restoration of a surviving church, where traces of important original details were erased and replaced with harsh and insensitive new features, which often failed to harmonise with the style of the original (87). J. R. Allen, in characteristically trenchant language, was only echoing what numerous Cambrians had said for 40 years when he remarked of the church at Llanddwyn, Montgomeryshire, destroyed to make way for Lake Vyrnwy, ‘It is impossible not to regret the necessary destruction of any relic of antiquity; but it would be a great relief in most cases to hear that a church had been blown up rather than allow it to be restored by a modern architect’ (88).

To Longueville Jones’s list of destructive factors one could add, by the 1860s, the effects on ancient sites of the growth in tourism facilitated by the opening up to urban populations of many parts of Wales by railways and improved roads. ‘A Traveller’, visiting Valle Crucis Abbey in 1863, found the place desecrated by tourists, ‘many of them of the lower class’ (89); other sites damaged by excursionists included Llansteffan Castle and Tre’r Ceiri, where ramparts were torn down by visitors (90). Tourism, however, brought with it economic benefits, and the need to encourage it could be used in arguments for the preservation of ancient monuments (91).

What, then, was the CAA’s contribution to the preservation of ancient and medieval sites and objects in Wales? It cannot be claimed that its success in saving buidings and sites was anything but spasmodic and ineffectual. Occasionally the CAA intervened directly as a body to preserve antiquities in danger of destruction. In 1847 it bought some coffin lids from Flint Church, with the intention that they should be placed in ‘some local Museum for national and county antiquities, which it is hoped may, at some future time, be established in Flintshire’ (92); in 1897 an early Christian cross at Penmon was removed from exposure to the weather at the CAA’s expense. In 1868 the CAA was offered the leases of Denbigh Castle by the Office of Woods and Forests, but the offer was declined, on the grounds that the it would be unpopular with the people of Denbigh (93). On some occasions funds were launched by the CAA to protect particular monuments. The first was started at the Aberystwyth meeting in 1847 in aid of Clynnog Fawr Church; others were to repair the churches at Llandudno and Aberdaron, though in the end the restoration of both was due to factors other than the CAA: a Birmingham solicitor offered to restore Llandudno Church at his own expense, and the church at Aberdaron was restored largely through the efforts of the villagers themselves (94). Towards the end of the century further funds were launched, with more success, since the CAA itself had more resources at its disposal; most notable was the fund to restore the hill-fort at Tre’r Ceiri, which was administered by a sub-committee set up for the purpose (95).

Funds or grants, however, were not the CAA’s usual method. More often it or its members sought to influence those responsible for ancient monuments by remonstration, petition and protest. This was most effective when CAA members visited sites during the annual summer meeting. The tombstones at Llantwit Major were saved from destruction after representations by members during a visit in 1849; a visit to Carew Castle in 1852 resulted in the restoration of a window; another to Holywell in 1857 led to the repair of St Winefrede’s Well (96). Nevertheless, successful interventions of this kind were never as frequent as Longueville Jones and his successors might have wished. Instead they had to be content with general exhortations to the gentry to take a more responsible and enlightened attitude to the monuments on their land, as, for example, ‘The preservation of the monuments of the former greatness of our country ought to be esteemed as one of the peculiar privileges of our aristocracy…’ (97), or, ‘It cannot be too strongly impressed upon the nobility and gentry of the land that they are, by virtue of their station, the natural conservators of the historical monuments of their country, and that they are bound to protect them, even at the expense of their money and their leisure’ (98). They advocated an educative process by which a concern and respect for antiquities was passed down from landowners to their agents, from agents to tenants, and from tenants to labourers (99). These hopes were often unfulfilled: the pages of Arch. Camb. contain more reports of monuments damaged or destroyed than reports of monuments preserved through the prompt action of knowledgeable gentry.

The failure of the CAA to make a significant impact on the preservation of antiquities may be attributed to several factors. Firstly, as a voluntary and unofficial organisation, it was in no position to back up its protests with the force of law. As the controversies surrounding the Ancient Monuments Bills showed, the rights of a landowner to treat monuments on his property in any way he pleased was a principle so dear to the hearts of government, capitalists and gentry alike that to challenge it could be regarded as an outright attack on the existing social system. There was one public body before 1882 which could and did intervene to preserve monuments. This was the Commission of Woods and Forests, which was responsible for the crown castles. From 1845 to 1847 it employed Anthony Salvin to restore Caernarfon Castle, at a final cost of £1,742, and repaired Harlech and Denbigh castles; it also played a part in the preservation of the town gates of Tenby (100). The expenditure involved in these projects was clearly beyond the scope of poorly-funded voluntary organisations, and some of the more thoughtful members of the CAA advocated a more active role in the preservation of antiquities on the part of the State. They could point to the French government as an example of successful official intervention (101). In 1847 J.O. Westwood wrote, ‘…these monuments of past ages, are the property of the public; and, as such, ought not only to be subject to their examination, but also to be entrusted to their care – of course with proper protection’ (102).

When at last the Ancient Monuments Protection Act was passed in October 1882 (the first bill had been introduced in 1873), its provisions were too weak to improve matters significantly. In particular it conferred no powers on the Commissioner of Works or the Inspectors of Ancient Monuments allowing them to take into State care the scheduled monuments without their owners’ permission. Of the fifty monuments, all of them prehistoric, listed in the schedule, only three were in Wales. J.R. Allen, aware of the deficiencies of the Act, proposed that the Inspector would be better employed if he could commission reports by members of local antiquarian societies, ‘who have the great advantage of possessing sources of information not open to any one else, and of being in direct communication with the owners of the properties on which the monuments are situated’ (103). The first Inspector, General Pitt-Rivers, or his assistant visited Wales four times between 1884 and 1890, partly to record monuments, partly to persuade their owners to place them in state custody (104). At his death in 1900 26 of the scheduled monuments had been taken into state protection and 17 monuments had been added. An Act of 1900 extended the scope of the original Act to include medieval monuments, and it also allowed county councils to take monuments into guardianship, but it was not till 1913, with the passage of a new measure, the Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act, that compulsory powers to protect monuments superseded the permissive provisions of earlier legislation.

Another important result of the Act was the appointment of an Advisory Board on Ancient Monuments for Wales and Monmouthshire. In 1910 the post of Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments, vacant since the death of Pitt-Rivers, was filled by the appointment of Sir Charles Peers, who inaugurated a period of systematic work in identifying and scheduling important ancient monuments. By 1931, when Wheeler reviewed the effects of the Act, 400 monuments in Wales had been scheduled: ‘At a pace which has set the Ancient Monuments Department reeling, castles, monasteries, and other ancient structures have passed into the hands of the State, and it is now impossible to travel many miles in Great Britain without encountering the handiwork of that excellent department’ (105). As Wheeler suggests, one of the major reasons for this trend was the impoverishment of many landowners after the First World War and their consequent eagerness to be relieved of the maintenance of ancient buildings on their property; more generally, one could point to the shift in social relations in the years around the War and the vastly increased importance of the state, especially after the reforms of the pre-war Liberal government associated with Asquith and Lloyd George.

The CAA’s role in all this was minor. All its members could do was suggest to the Inspectors that particular monuments should be afforded government protection. In the case of Tre’r Ceiri its efforts were conspicuously unsuccessful: the government refused its request to schedule the hill-fort as a protected monument under the provisions of the 1882 Act, even though the owner, R. H. Wood, was eager for it to do so.

If the CAA proved ineffective in the cause of the protection of sites, it was no more successful in the preservation of ancient objects. Since it lacked a permanent home or headquarters, it was unable to acquire and maintain a museum of Welsh antiquities. In 1850 the Committee decided that any property the CAA might acquire was to be deposited in museums already formed, at Caernarfon, Shrewsbury and Swansea (106). It is true that at most annual meetings, ‘temporary museums’ were arranged for the instruction and amusement of members and their families, but most of the exhibits were simply loaned for the occasion by private individuals, and the collections arranged seldom had any common theme. At the time of the CAA’s foundation the collecting of antiquities was still largely a private affair. The only non-private museums in existence in Wales were those belonging to the philosophical societies at Neath and Swansea, and a small but significant collection established in Caernarfon in the 1840s by a small local antiquarian society, which was augmented by finds from the Segontium excavation of 1846. The fate of the Caernarfon collection illustrates the precariousness of such museums. In 1848 it was well cared for by the ‘Natural History Society of the Counties of Caernarvon, Merioneth and Anglesey’, under the curatorship of James Foster. After Foster’s death in 1858 the collection began to deteriorate. Coins were recorded as missing from it in 1860; later parts of it were dispersed and distributed about the town; the remainder had been removed to the Castle, where they were inaccessible (107).

The Cambrians welcomed the establishment of local museums from the beginning. The founding of public museums was, indeed, one of the cornerstones of Longueville Jones’s blueprint for a systematic policy for Welsh archaeology (108). Excavations were useless unless the finds from them could be preserved in public collections, since otherwise ‘they are absorbed in private collections – unclassified, unstudied, and unknown; they remain there during the lifetime, perhaps, of the possessor, and at his death they are either sold, or given ultimately as playthings to children’ (109). An anonymous writer suggested in 1852 the establishment of museums, perhaps under the auspices of local societies, in the principal town of each county (110). J.O. Westwood, in line with his heretical belief that museum objects, although found on private property, were really the property of the public, proposed that collections should be housed in the public building of each county town (111). Individual members often spoke in support of the establishment of local museums (112), and were sometimes instrumental in setting them up, as in the case of Tenby Museum (113).

The idea of a national museum for Wales was also aired early in the CAA’S existence. It was regarded as especially desirable in view of the reluctance of the British Museum to collect and display British antiquities (114); the British Museum’s Department of British and Medieval Antiquities was not formed until 1866 (115). Welshmen were also conscious that Ireland had, in the museum of the Royal Irish Academy, the nucleus of a national collection as early as 1848 (116). However, little was done until 1870, when a letter was read at the annual CAA meeting at Holywell from the Mayor of Caernarfon, Llewelyn Turner, suggesting that the collection in Caernarfon Castle should form the basis of a national museum. The Secretary ‘was directed to express the approval of the proposed plan, and to state that the Association would do all in its power to promote its success’ (117). Work was started on preparing for the new museum, but in 1879 the collection was still described as ‘inaccessible’, and by 1890 the attempt had been abandoned (118). Meanwhile rival claims had been made for Tenby and Welshpool as the site for a national museum, with no result (119). This lack of progress was reflected in J.R. Allen’s comment in 1890, ‘…it is not a pleasant reflection for patriotic Welshman to think that Welsh antiquities are appreciated everywhere except in Wales. The Cambrian Archaeological Association might well improve the present not particularly creditable state of things by endeavouring to establish a Museum of National Antiquities for Wales’ (120). But the movement for a National Museum, when it came, did not come from the CAA, but from the Cymmrodorion Society, the University Colleges, Welsh MPs and local authorities. After a prolonged campaign from 1903 onwards the Conservative government assented in 1907 to the foundation of a National Museum in Cardiff, although it was not until 1927 that the new building was opened (121).

A further factor inhibiting the CAA from taking decisive action, apart from its lack of a permanent home and of legal or administrative powers, was the remoteness of its officials from events, movements and people at a local level. Again and again, it could do no more than react to events that had already occurred, even if it heard about them in the first place. The chief means by which the Association was to keep in touch with local archaeological matters were the Local Secretaries, an institution taken over from the Archaeological Institute (122). Their function was to ‘attend to the interest of the Association in their several districts’. By the time of the first annual meeting at Aberystwyth in September 1847, fourteen local secretaries had been appointed, one for each Welsh county, except Brecknockshire and Montgomeryshire, and one each for three of the Border counties. Members were encouraged by the editors to report any ‘antiquarian information or discoveries’ to the local secretaries, and to ‘consider nothing too insignificant for communication, if duly authenticated’ (123). At Caernarfon in 1848 it was decided that a second local secretary should be appointed for each county (124). It became obvious, however, that the mere existence of local secretaries did not of itself ensure adequate communications between the CAA and the people of Wales, and at the special Gloucester meeting in March 1850 a more ambitious scheme was put forward, whereby local committees were to be set up in various parts of Wales. ‘Where it is practicable’, the new rule ran, ‘the Local Committees shall cause meetings to be held in their several districts, and shall encourage the formation of museums’ (125). But at the Dolgellau meeting in August 1850 the Committee had to confess that no local committees had yet been formed, and, as it turned out, none ever were.

The system of local secretaries continued, but it never operated in the way Longueville Jones and his colleagues wanted. Many appointees regarded the post as a sinecure, and were totally ineffective, either in reporting discoveries and other events to the Association, or in boosting its local membership. The editors called continually, to little avail, for local secretaries to contribute notices to Arch. Camb., and as the years passed the condemnation of their apathy became almost a ritual cry: ‘The Editors…are obliged to complain of the very small assistance they receive from the local secretaries. With two or three exceptions, the Local Secretaries never communicate with the Editors from one year’s end to another’ (126). In 1888 the editors were so exasperated that they sent a letter to each local secretary, urging them to perform their duties more efficiently, by reporting new discoveries, sending newspaper cuttings relating to archaeological matters, calling attention to the destruction of monuments and the restoration of churches, and seeking out new recruits to the Association (127). The response was less than energetic. The following year the editors remarked scornfully of the ogham stone found at Eglwys Cymyn, Carmarthenshire, ‘It does not reflect much credit on the local secretaries of the Cambrian Archaeological Association that it should be possible for an inscribed stone to remain unnoticed for years until attention is called to it by some stranger who casually visits the place where it is to be found. There can be little hope of archaeology taking its place on an equal footing with other exact sciences if its methods are so slipshod’ (128). One of the local secretaries, D. Griffith Davies, retorted that the CAA authorities were partly to blame for the unsatisfactory situation, because they had never defined accurately the duties of local secretaries. He also implied that what reports the local secretaries did send were actually unwelcome: ‘Should he [the local secretary], in his archaeological zeal, and the enthusiasm begotten of his first year of office, display a little more than the usual activity, he too often meets a reception which is calculated to cool his ardour, and force him to assume that lethargic state which has called forth his editor’s rebuke’ (129). The editorial rebukes gathered pace in the following years, until in 1909 it was admitted that no communication had been received from seven Welsh counties for at least two years (130). By this time the paucity of contributions about local discoveries was partly attributable to the emergence of thriving county and local societies, whose publications normally carried such notices (131).

From its beginning the CAA had encouraged the growth of local antiquarian societies. Longueville Jones, in his initial manifesto, urged the establishment of museums and local societies in ‘at least twelve towns’ in Wales, where a sizeable body of cultured gentry could congregate, even though, as he admitted, there was at the time ‘hardly any antiquarian body to be found in the Principality possessing features of vitality and activity’ (132). Arch. Camb. was quick to print the proceedings of the inaugural and first annual meetings of the Caerleon Antiquarian Society (133), and an invitation was extended to other antiquarian societies in Wales to send communications of their activities (134). An (abortive) attempt by Archdeacon John Williams of Llandovery to found a society in Carmarthenshire in 1849 was welcomed as a model for other societies (135). But Longueville Jones’s ambitions went beyond a mere friendly notice of proceedings. Unknown to the readers of Arch. Camb., he had written to other antiquarian and scientific societies in Wales in 1848 to suggest a union of all literary and scientific societies in Wales into one society. The reply of the Neath Philosophical Society was unambiguous. Its members declined the offer ‘fearing that such an amalgamation, by destroying the individuality of these Societies, would greatly weaken the local interest felt in them’ (136). The replies of other societies contacted by Longueville Jones were presumably similar, and no more is heard of amalgamation. The appearance of new societies continued to be welcomed. The Powysland Club, founded in 1867, mainly by CAA members, received particularly sympathetic treatment (137). Towards the end of the century the policy of laissez-faire which the CAA had employed hitherto began to give way, as the idea of professionalism in archaeology gained ground, to a wish to systematise both the relations between itself and local societies and the structure of the societies in general. The most forthright statement favouring intervention appeared in a review in Arch. Camb.: ‘It is a great pity that some means cannot be found for either suppressing some of the smaller societies altogether, or of making them attend to one special object’ (138). This kind of feeling had hardened by 1919 into a highly patronising attitude to local societies, which were now regarded as entirely lacking the professionalism required for the conduct of serious archaeological work: ‘…every encouragement should be given to the formation of local antiquarian societies and field clubs, not for the purpose of excavation – Heaven forbid – and not for the retention of casual ‘finds’ which are better kept elsewhere, but for the closer study of archaeological problems and for sympathetic assistance and cooperation in the preservation of archaeological remains’ (139).

Meanwhile the national movement for the coordination of local societies had culminated in 1889 in the formation, on the initiative of the Society of Antiquaries of London, of the Congress of Archaeological Societies (140). The Congress acted as the spokesman of the societies, for example, to the government on the preservation of ancient monuments, and through its Earthworks Committee publicised the destruction, preservation and excavation of earthworks throughout the country. The CAA sent two delegates to the first preliminary conference, but later declined to allow its name to be added to the register of affiliated societies, ostensibly on the grounds that it could never admit the right of the Society of Antiquaries ‘to send its officials to Wales to dictate how explorations shall be conducted’ (141). In reality, as he himself makes abundantly clear, J.R. Allen, aggrieved that his own plan for the national organisation of archaeological research had been rejected by the Council of the Society of Antiquaries, was personally responsible for the CAA’s change of heart (142). He suspected the Society of using the local societies for its own purposes, ‘taking every advantage to be gained from them, and giving next to nothing in return’.

As the new century progressed this isolationism on the part of the CAA became increasingly irrelevant, as professional attitudes and practice gradually displaced the amateurism of the antiquarians. The work of the Liverpool Committee for Excavation and Research in Wales and the Marches has already been noted. Later the National Museum of Wales took up the initiative in excavation, under the direction of John Ward, Mortimer Wheeler, Cyril Fox and V.E. Nash-Williams. In 1920 the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire at last established a lectureship in archaeology, held initially by the Keeper of Archaeology at the National Museum. Two years later the University of Wales Board of Celtic Studies was set up, with the study of archaeology as one of its chief concerns. After 1913 more effective steps could be taken to preserve the ancient monuments of Wales through the agency of the Ancient Department Monuments Division of the Office of Works, while the recording of antiquities was by now in the hands of the Royal Commission on Ancient Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire (143).

Slowly, then, the functions which the CAA had fulfilled or had aspired to fulfil were stripped away, until the only clear archaeological role left to it was to provide, in Arch. Camb., a convenient receptacle for the excavation reports of the new generation of professional archaeologists.

Throughout the nineteenth century the CAA had survived as the national archaeological organisation, almost without challenge (144). Its achievements were considerable: it succeeded in bringing together the best archaeological minds in Wales and providing a forum for their reports and debates, and it played a part in stimulated interest in archaeology among the middle classes. But it suffered from several serious limitations, which the local Welsh archaeological societies were quick to exploit. Glyn Daniel’s assertion that the history of archaeology in Wales is the history of the CAA contains much truth, but overlooks the real contribution made by these societies (145).

Note

This paper was originally written in the early 1980s and does not incorporate relevant scholarship published since then. Corrections and updates would be welcome.

References

1. J.E. Lloyd, ‘Introduction’ in V.E. Nash-Williams (ed.), A hundred years of Welsh archaeology, Gloucester, [1946].

2. Owain W. Jones, ‘The Welsh Church in the nineteenth century’ in David Walker (ed.), A history of the Church in Wales, Penarth, 1976, p.147-48.

3. Arch. Jnl., vol. 1, 1844, p.380-81.

4. Arch. Camb., 1846, p.1.

5. Arch. Camb., 1846., p.11.

6. Arch. Camb., 1846, p.283.

7. Arch. Camb., 1847, p.462.

8. Arch. Camb., 1849, p.9-12, 94-100, 160-67, 291-94.

9. Arch Camb., 1846, p.40.

10. Arch. Camb., 1846, p.7.

11. Arch. Camb. 1846, p.7.

12. Arch. Camb., 1846,p.12.

13. Arch. Camb., 1846, p.13.

14. Arch. Camb., 1846, p.28 ; 1847, p.355.

15. Sir Ben Bowen Thomas, ‘The Cambrians and the nineteenth-century crisis in Welsh studies’, 1847-1870′, Arch. Camb., 1979, p.1-15.

16. Over one fifth of the members of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society were clergy in 1876 (Kenneth Hudson, A social history of archaeology: the British experience, London, 1981, p.18.)

17. Arch. Camb., 1867, p.76.

18. R. Goring Thomas to H.L. Jones, 24 August 1848. National Library of Wales NLW MSS Cambrian Archaeological Association, Letter-book Ll, f.29 r.

19. Arch. Camb., 1867, p.76.

20. Herbert M. Vaughan, The South Wales squires: a Welsh picture of social life, London, 1926; Glanmor Williams, ‘The gentry of Wales’ in Glanmor Williams, Religion, language, and nationality in Wales, Cardiff, 1979, p.148-170.

21. Arch. Camb., 1846, p.279.

22. Arch. Camb., 1856, p.344; 1871, p.94.

23. Arch. Camb., 1847, p.180.

24. Arch. Camb., 1847, p.352.

25. Arch. Camb., 1848, p.351. See Evelyn Lewes, Out with the Cambrians, London, 1934 for an interesting view of the social activities of the CAA.

26. Thomas Wakeman to H. L. Jones, 3 October 1848. NLW MSS CAA Letter-book L1, f. 24 v.

27. Arch. Camb., 1866, p.363.

28. Arch. Camb., 1908, p.108.

29. Arch. Camb., 1857, p.216.

30. Arch. Camb., 1893, p.85; 1894, p.69; 1896, p.65; 1897, p.76; 1898, p.79.

31. Arch. Camb., 1896, p.65; 1897, p.76.

32. Arch. Camb., 1903, p.12-15.

33. Arch. Camb., 1903, p.73-4.

34. Donald Moore, ‘Cambrian antiquity; precursors of the prehistorians’ in George C. Boon and J.M. Lewis, (eds.), Welsh antiquity: essays mainly on prehistoric topics presented to H.N. Savory upon his retirement as Keeper of Archaeology, Cardiff, 1976, p.215.

35. Arch. Camb., 1850, p.66-7; 1852, p.71.

36. Arch. Camb., 1856, p.68-9; 1857, p.151-72.

37. Arch. Camb., 1853, p.180-88.

38. Strata Florida: Arch. Camb., 1887, p.290-99; Talley: Arch. Camb., 1892, p.160-63; Strata Marcella: Arch. Camb., 1892, p.4.

39. Liverpool Committee for Excavation and Research in Wales and the Marches, First annual report, 1908, Liverpool, 1909.

40. Trans. Hon. Soc. Cymm., 1910-11, p.115-29.

41. Trans. Hon. Soc. Cymm., 1910-11, p.129.

42. Robert Carr Bosanquet, Letters and light verse, edited by Ellen S. Bosanquet, Gloucester, 1938, p.178.

43. J. Ward to G.G.T. Treherne, 6 August 1918. NLW MSS 10129D; cf. John Ward, The Roman fort of Gellygaer, London, 1903, p.14-19 for an account of organisational difficulties.

44. Sir Mortimer Wheeler, Still digging: interleaves from an antiquary’s notebook, London, 1955, p.73, 75-6.

45. Arch. Camb., 1846, p.421.

46. Arch. Camb., 1848, p.187-90.

47. Arch. Camb., 1860, p.322-24.

48. Arch. Camb., 1848, p.5.

49. Arch. Camb., 1848, p.5-6.

50. Arch. Camb., 1853, p.275; 1854, p.81-7; 1865, p.310-11.

51. Arch. Camb., 1850, p.81-9.

52. Arch. Camb., 1850, plate opp. p.174.

53. Arch. Camb., 1851, p.274-81.

54. Arch. Camb., 1852, p.65-8, 96-104.

55. Arch. Camb., 1851, p.219-225.

56. Glyn Daniel, ‘Introduction’ in I.Ll. Foster and Glyn Daniel (eds.), Prehistoric and early Wales, London, 1965, p.14.

57. Arch. Camb., 1846, p.16.

58. Arch. Camb., 1853, p.285.

59. Arch. Camb., 1849, p.1; 1851, p. 163, 326 n.; 1869, 78.

60. Arch. Camb., 1847, p.186; Caledonia Romana: Arch. Camb., 1846, p.197.

61. Arch. Camb., 1847, p.280.

62. Arch. Camb., 1847, p.376; 1851, p.167.

63. Arch. Camb., 1853, p.278.

64. Arch. Camb., 1869, p.79.

65. e.g. by W.B. Dawkins and Pitt-Rivers on Offa’s Dyke in 1869 (Arch. Camb., 1873, p.214-16) and by W.O. Stanley on Cytiau’r Gwyddelod near Holyhead (Arch. Camb., 1868, p.385-400.)

66. Arch. Camb., 1888, p.187-203.

67. Arch Camb., 1893, p.56-61; 1894, p.70.

68. Arch. Camb., 1895, p.1-4.

69. Arch. Camb., 1895, p.238; 1896, p.266-7.

70. Arch. Camb., 1896, p.63.

71. Arch. Camb., 1896, p.266-7.

72. Excavations: Arch. Camb., 1897, p.41-4; Pembrokeshire. bibliography: A list of printed books treating of the County of Pembroke, 1897.

73. Arch. Camb., 1901, p.156.

74. Arch. Camb., 1907, p.126,

75. e.g. Arch. Camb., 1917, p.135.

76. Arch. Camb., 1846, p.2.

77. Arch. Camb., 1846, p.3-16.

78. Arch. Camb., 1859, p.304-5.

79. Arch. Camb., 1902, p.154-5; 1906, p.70.

80. Arch. Camb., 1869, p. 190-91.

81. Arch. Camb., 1848, p.187; 1850, p.222-23,224; 1853, p.5, 180; 1882, p.236-37; Arch. Jnl., vol. 2, 1845, p.76-7.

82. Arch. Camb., 1852, p.157.

83. Arch. Camb., 1857, p.56.

84. Arch. Camb., 1851, p.162-63; 1857, p.197; 1865, p.196, 310.

85. Arch. Camb., 1846, p.10.

86. Arch. Camb., 1850, p.164; 1864, p.125.